A Different Sort Of Crisis

Ioane Teitiota, a citizen of Kiribati (an island nation in the Micronesia subregion of Oceania in the central Pacific Ocean), wanted to take asylum in New Zealand as a Climate Refugee in 2013. He reportedly claimed that the effects of Climate Change, particularly rising sea levels, made Kiribati uninhabitable. However, New Zealand rejected his application, stating that he was not facing persecution as defined by the Refugee Convention. The concerned authorities in New Zealand also deported Teitiota and his family back to Kiribati in September 2015.

Later, Teitiota filed a communication with the UN Human Rights Committee (HRC), arguing that New Zealand had violated his Right to Life under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. In October 2019, the HRC declared Teitiota’s communication admissible, but found no violation of his Right to Life. It may be noted that the timeframe of 10-15 years for Kiribati to become uninhabitable did not satisfy the need for the risk to be real, personal and imminent. Although Teitiota failed to settle in New Zealand, his case raised important questions about the legal status of Climate Refugees or Climate Migrants.

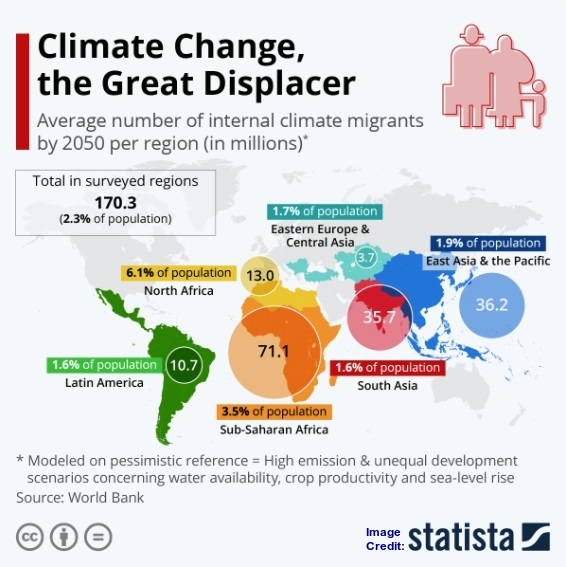

Teitiota is not alone. As per a latest study, the number of climate refugees would reach 1.2 billion (one-eighth of the total global population) by the end of 2050! People are often forced to leave their homelands due to war, ethnic conflicts, famine and floods. In the 21st Century, the global community has realised that Climate Change, too, can prompt people to leave their own countries.

According to data provided by the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in 2018, approximately 25 million people fled their homelands and sought refuge in other countries mainly because of violence, genocide, Human Rights violations and political oppression. The UNHCR further mentioned that two-thirds of those refugees came from five countries: Syria, Afghanistan, South Sudan, Myanmar and Somalia. Interestingly, more than 40 million people had to take shelters in other parts of their countries.

On the other hand, around 21.5 million people across the globe are displaced due to natural disasters or Climate Change. Although the UNHCR has acknowledged climate as a potential cause of the refugee crisis, it still considers five criteria – race, religion, nationality, ethnic conflict and political affiliation – for getting refugee status. The Climate Change Framework 2024-30, developed by the UNHCR, focusses mainly on protecting people fleeing climate-fuelled crises and building resilience in climate-vulnerable countries, with four main themes: assess, arrange, access and act. The UN agency has also decided to provide migrants or displaced people with humanitarian assistance and to create opportunities for living a healthy life, apart from taking Climate Change mitigation measures and initiatives to reduce greenhouse gases.

Although the UN created the Refugee Act in 1951 and the Refugee Protocol in 1967, the World Body is yet to ensure separate legal protections for climate refugees. Special importance was attached to the preservation of the natural environment after the 1972 Stockholm Conference. However, the problem lies elsewhere. Article 35 of the UN Charter outlines how UN member-states can bring disputes or situations to the attention of the Security Council or General Assembly. The primary role of the UNHCR is to protect refugees and those in need of international protection, with a mandate to supervise the application of international conventions related to refugees. Hence, proper protection measures for climate refugees have not yet been adopted at the international level.

The production, as well as use, of energy and the development of national culture are the current standards of civilisation, and also a common driving force. Therefore, increasing scientific awareness has become a difficult challenge as far as the use of energy is concerned. Syukuro Manabe of Japan and Germany’s Klaus Hasselmann jointly won the 2021 Nobel Prize in Physics, along with Giorgio Parisi of Italy, for their contributions to the physical modelling of Earth’s climate, quantifying its variability and reliably predicting Global Warming. Apart from raising awareness worldwide, it is also important to adopt the correct scientific method to deal with the climate refugee crisis.

It may be noted that Nauru, the world’s third-smallest country by land area (covering only 21sqkm), has decided to offer citizenship for USD 105,000 under its Economic and Climate Resilience Citizenship Programme. The move is aimed at raising funds to combat Climate Change and relocating its population of around 12,500 to higher ground as rising sea levels threaten its existence.

Boundless Ocean of Politics on Facebook

Boundless Ocean of Politics on Twitter

Boundless Ocean of Politics on Linkedin

Contact us: kousdas@gmail.com