Ancient Romans Considered Indian Spices As Luxury Item

The phrase “All roads lead to Rome” was literally true at the peak of the Roman Empire as people used to travel to the Italian capital even from India and the Middle East.

The main attraction of Rome is the Roman Forum (Foro Romano), which was the very heart of ancient Rome’s public life for centuries, hosting political, commercial, religious and daily activities, like speeches, trials and parades. The remains of this major archaeological site draw millions to its ruins between the Palatine and Capitoline Hills. The construction of the Basilica of Maxentius and Constantine, the last great civic basilica in the Roman Forum, began under Emperor Maxentius around 308 AD and was completed by his successor Emperor Constantine the Great after 313 AD. In ancient Rome, a basilica referred to a specific type of large, roofed public building used for judicial proceedings, commercial administration and public assembly, essentially a multi-purpose civic centre.

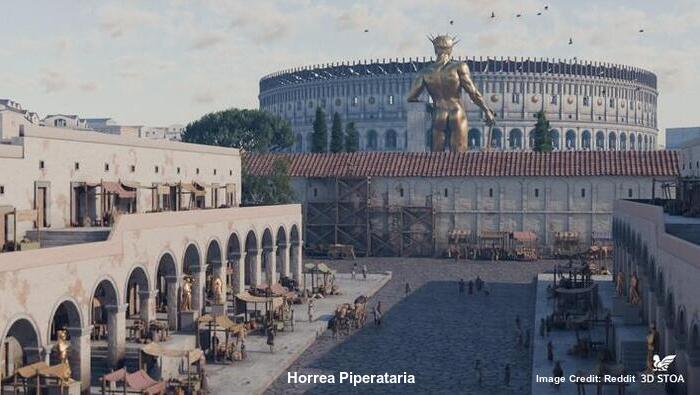

After entering the main entrance on the east side of the Roman Forum and proceeding along the ancient stone-paved highway, the Via Sacra, one can find the ruins of the Basilica Aemilia on the right. The Horrea Piperataria (or the warehouses of spices) was discovered here during archaeological excavations in 1923.

Black pepper was the most popular, as well as valuable, Indian spice in the Roman Empire. Hence, it was called black gold and used as a status symbol, a form of currency and demanded as ransom, with Romans importing massive quantities from Malabar Coast of India. Built by Emperor Domitian in 92 AD on the Velia hill, the imperial warehouses for valuable spices from places, like India, Egypt and Arabia, was a critical logistical hub for trade, medicine and rituals in ancient Rome. According to archaeologists, this massive complex had a multi-storied structure with at least 150 rooms arranged around two courtyards. There were also multiple tubs, probably for cleaning raw spices and herbs. The thick walls of the warehouses used to keep the temperature low. The Roman soldiers used to guard the Horrea Piperataria round the clock because the warehouses stored extremely valuable goods, like pepper, incense and medicinal herbs, from India and Arabia, making them high-security banks for luxury commodities.

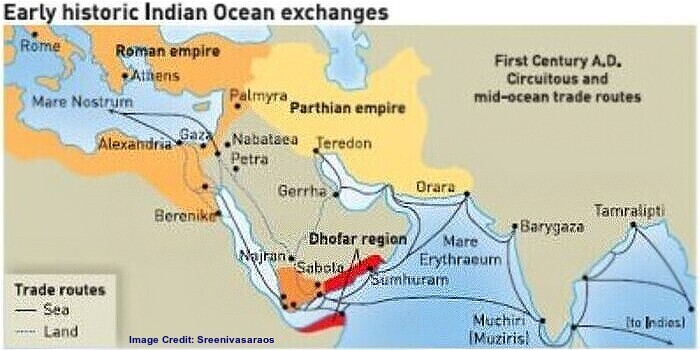

The spice trade between India and the West is ancient, starting over 4,000 years ago, predating the Silk Road and involving complex land, as well as maritime, routes through Arab middlemen before Europeans, like Vasco da Gama, established direct maritime links in the late 15th Century to bypass monopolies and access Indian spices, leading to intense colonial competition. A 2nd Century BC shipwreck found with Indian pepper suggests extensive direct maritime trade between the Roman Empire and the Malabar Coast of India. Gradually, the demand for Asian spices grew in Europe beyond just flavour, driven by beliefs in their powerful medicinal, ritualistic (incense, religious scents) and social properties (status symbol), alongside culinary uses.

Ancient Greek and Roman medical practices incorporated knowledge of and used Indian herbs, which were introduced through established trade networks. Greek physicians became expert herbalists and, along with Roman practitioners, used a variety of plants for a wide array of ailments. Specific Indian plants were used as antidotes to poisons and pain relief, to cure eye and gynaecological problems. In the first 28 chapters of his De materia medica (a five-volume Greek encyclopaedic pharmacopeia on herbal medicine and related medicinal substances), Greek physician Pedanius Dioscorides mentioned various Indian herbs. Hence, the area around the Horrea Piperataria emerged as a renowned medical district in ancient Rome, favoured by doctors because of the availability of medicinal herbs and spices. Asclepiades (sometimes called Asclepiades of Bithynia or Asclepiades of Prusa; 129/124 BC – 40 BC), a Greek physician, used to collect herbs from this warehouse.

By the 1st Century AD, the Romans were well aware of the course of the monsoon winds in the Indian Ocean and relied heavily upon them for direct, large-scale trade with India. Augustus (born Gaius Octavius), the founder and first Emperor of the Roman Empire who ruled from 27 BCE until his death in 14 CE, significantly boosted Indo-Roman trade by creating stability, removing barriers and investing in infrastructure, like desert roads, leading to a massive increase in maritime traffic (from -20 to 120+ ships per year) between Egypt’s Red Sea ports and India, flooding Roman markets with Eastern luxuries and fostering diplomatic ties.

Greek geographer Strabo famously mentioned in his Geography (Book 16, Chapter 4) that after the Romans took over Egypt, a massive trade boom with India began, with up to 120 ships sailing annually from the port of Myos Hormos to India, highlighting the immense wealth and connectivity of the early Roman Empire’s maritime trade routes. The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, a 1st Century maritime guide, details numerous Indian ports, with around 24-26 key trading centres mentioned from the Indus region down to the southern tip, like Barygaza (Bharuch), Muziris, Puhar (Camera) and Poduca (Puducherry), highlighting India as a central hub for spices, pearls, textiles and other goods in the ancient Indian Ocean trade network. The ancient seaport of Muziris, located in present-day southern Indian Province of Kerala, was a cornerstone of the ancient maritime spice trade.

Later, the volume of India’s trade with the Roman Empire far exceeded that with Hellenistic Greece. Historical sources and archaeological evidence confirm a massive and direct maritime trade network that flourished during the Roman era, particularly from the 1st Century BCE to the 2nd Century CE. The reign of Augustus marked the beginning of the golden age for Indo-Roman trade as merchant ships from India, carrying spices, cotton clothes and various luxury goods, used to sail across the Indian Ocean to Egyptian ports on the Red Sea, most notably Berenike and Myos Hormos. From the Red Sea ports, camel caravans transported the goods across the eastern desert of Egypt to reach the Nile River. Once the goods reached the Nile, they were loaded onto boats and sailed north to the bustling port city of Alexandria. From Alexandria, the valuable cargo was then distributed throughout the Roman Empire. The Horrea Piperataria stored the valuable imported spices and herbs, and the Roman State controlled the trade and taxation of these goods, which helped to regulate supply to the city’s elite and institutions.

Indian spices were a highly prized luxury item for ancient Romans. In addition to black pepper, white pepper, pipul, turmeric, cloves, cardamom and bay leaves, the Romans used to import various herbs from the South Asian nation. Pliny the Elder mentioned the practice of adulterating spices, a fraud driven by the high demand and exorbitant cost of genuine Indian goods, like pepper, in the Roman Empire. In his encyclopaedia Natural History, Pliny lamented the immense drain of Roman gold to India to pay for luxuries, a trade he estimated cost the Empire 50 million sesterces annually. The high value of spices created a strong economic incentive for dishonest merchants to engage in fraud. In his Roman cookbook De Re Coquinaria, ancient Roman gourmand Apicius reportedly mentioned nine types of Indian spices. Not only by the rich, but also the fairly well-off city dwellers and Roman soldiers used to purchase Indian pepper. Although the Roman Empire had long imposed a 25% import duty on foreign goods, there was no duty on Indian pepper. This suggests that the ancient Roman society considered Indian black pepper as an essential ingredient.

One has to walk through the Via Sacra (or the Sacred Street) – the main street of ancient Rome, leading from the top of the Capitoline Hill through some of the most important religious sites of the Roman Forum to the Colosseum – to feel the past. The Vicus ad Carinas, one of ancient Rome’s oldest and most important streets, ran past the Basilica of Maxentius and the Temple of Romulus (part of the Santi Cosma e Damiano complex) in the Roman Forum, with the Basilica built over part of the road using a tunnel, integrating the ancient route into its structure, near eastern side of the Forum. Archaeologists have dug tunnels beneath the basilica to access the Horrea Piperataria. Inside the tunnel, one can find a transparent glass walkway under her/his feet. There is a 2,000-year-old ancient floor of burnt bricks underneath the walkways. Also, there are ancient basins for cleaning spices and fragments of underground sewers near the tunnel. Tourists can watch two documentaries on the history of Horrea Piperataria here.

The scent of Indian black pepper still lingers in the cracks of broken bricks inside the Horrea Piperataria, as the those bricks serve as a physical testament to an era when exotic spices, like Indian black pepper, were a cornerstone of commerce and daily life in Rome.

Meanwhile,

Boundless Ocean of Politics on Facebook

Boundless Ocean of Politics on Twitter

Boundless Ocean of Politics on Linkedin

Contact us: kousdas@gmail.com