Tariff War, BRICS & Global Political Economy

Some economists and trade theories believe that Free Trade is generally beneficial mainly because of increased efficiency, lower prices and division of labour. Although they are of the opinion that it is better to avoid over-analysing global trade, as well as its trends, and let them unfold naturally; the idea is not universally accepted. In fact, the Global Political Economy does not move in a straight line. Instead of a linear progression, it makes constant shifts, influenced by a multitude of factors and actors, leading to unexpected outcomes, as well as transformations. Various factors, like temporary losses, future gains, the financial strength of the market, investment opportunities, etc., have made the nature of global trade quite complex and unpredictable. Hence, global trade has become a perpetual conflict between short-term and long-term interests.

James Brander and Barbara Spencer penned some remarkable papers on international trade, popularly known as the Brander-Spencer Model, in the 1980s. In the context of a particular market system, they explained that profits could be increased by making slight changes in trade policy. In other words, the Brander-Spencer Model suggests that strategic trade policies, like export subsidies, can be used to shift profits towards domestic firms and to increase national welfare in certain imperfectly competitive markets. It may be noted that Brander and Spencer concentrated not on a competitive market, but on Oligopoly (a market structure dominated by a small number of firms, giving them significant control over prices and output) where countries that join the trade are financially strong enough and can influence the market.

In reality, powerful nations use various strategies against each other as far as the trade policy is concerned. Imposing tariffs on foreign products (and also providing domestic producers with subsidies) is a part of the strategy and it is called Reciprocal Tariff or Reciprocal Dumping. The US and China have been engaged in such a tug-of-war for several years. US President Donald John Trump recently added a different dimension to this game by imposing 50% tariffs on products from India and Brazil mainly to capture the Third World market.

Russia and the US have been engaged in an economic war for decades. Reflections of the Cold War can also be seen in the ongoing Russia-Ukraine War. The Brander-Spencer Model suggests various possibilities for capturing the market of the third party (Ukraine in this particular case). One of them (Russia and the US) is to temporarily oust competitors from markets of the third party by arranging temporary subsidies. In economic terms, it is called Profit Shifting (when multinational companies reduce their tax burden by moving the location of their profits from high-tax countries to low-tax jurisdictions and tax havens).

Interestingly, President Trump has made no such move. He neither provided the American sellers (who sell their products in the Indian market) with subsidies, nor imposed tariffs on Russia (the main competitor of the US). Instead, the US President increased import duties on goods manufactured in India and tariffs on Indian products exported to the US. In July 2025, President Trump imposed 25% tariffs on Indian imports. On August 6, he increased tariffs on many Indian goods by 25%, bringing the total tariffs up to 50%. As expected, the move has raised concerns about its impact on the Indian economy and the stock market. It should not be considered as an economic policy, but a policy to put a country under tremendous economic pressure. It is basically a leverage against the South Asian nation, potentially leading to the removal of India from the US market (because of the possibility of losing the Indian market).

India relies heavily on foreign countries for its defence needs, with about 65-70% of defence and military equipment being imported. Wars (or war-like situations), naturally, drive up demand for defence equipment, weapons and related technologies, allowing countries (like the US, Russia, France, China and Germany) or companies that export weapons and military technologies to gain advantage. In such a scenario, if India continues to import Russian defence equipment, the US will lose the Indian market. Even as the import of US defence equipment to India has slashed in recent times, India has re-written procurement laws to block US suppliers. Hence, President Trump has imposed an additional 25% tariff on India for its purchases of Russian products, including crude oil and defence equipment. The equation is simple: The US can regain the Indian market only if India stops buying products from Russia amid fears of losing the US market.

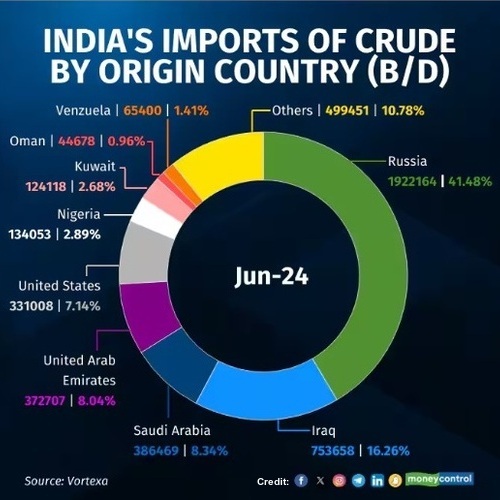

President Trump can hope so as reciprocal, as well as punitive, tariffs will certainly give some jolt to India’s economic progress. However, one should not forget that there is also a huge demand for crude oil in India. Russia has already become India’s largest oil supplier, with its share of India’s total oil imports surging from 2% in FY20 to 35.1% in FY25. This shift is largely due to Russia offering discounted crude oil following Western sanctions after the Ukraine conflict, making it a more cost-effective option for India. Perhaps, the US President ignores the fact that if India switches to importing oil from somewhere else at a higher cost, the American consumers will likely feel the hit, too. It may be noted that some of the Russian crude oil sent to India is then refined and exported back out to other countries (as sanctions on Moscow do not include products refined outside Russia).

Analysts are of the opinion that BRICS (an intergovernmental organisation comprising 10 countries: Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa, Egypt, Ethiopia, Indonesia, Iran and the UAE) would help India to overcome the crisis. Reports suggest that President Trump’s tariff war has brought the BRICS nations closer as they are planning to jointly counter the US trade policy.

The BRICS group has emerged as a major political force in the last couple of decades, building on its desire to create a counterweight to Western influence in global institutions. The BRICS nations have also started exploring the possibility of introducing a common currency for international trade among themselves. The common currency would facilitate trade, travel, education and cultural exchanges among member-countries, apart from helping them to present themselves as more reliable trade and investment partners to others.

Also, there are several other issues, such as China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), US-China trade war, India’s emergence as the world’s fourth largest economy, the role of Russia as a global power, and the joint dominance of India and China in the human capital market. These issues could slightly shift the global economic axis in the coming days, creating troubles for the US.

Boundless Ocean of Politics on Facebook

Boundless Ocean of Politics on Twitter

Boundless Ocean of Politics on Linkedin

Contact us: kousdas@gmail.com