Stemming From The Same Origin

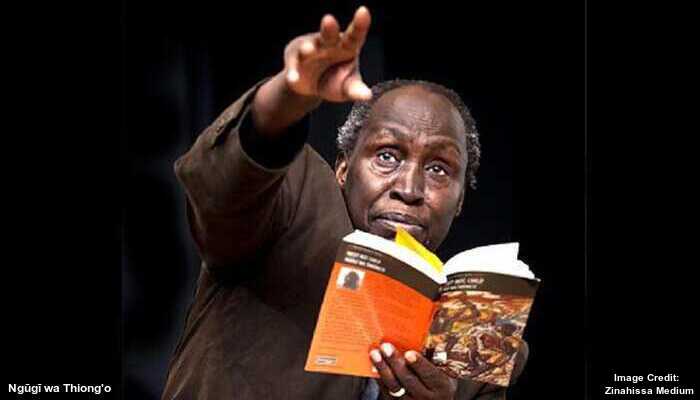

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o (born James Ngugi; January 5, 1938 – May 28, 2025), the Kenyan author and academic who has been described as the leading novelist of East Africa and also an important figure in modern African literature, took his last breath in Buford, Georgia, the US in May 2025. The global community celebrates African World Heritage Day also in May (5) every year. Incidentally, the first ship carrying indentured labourers from the eastern Indian port city of Calcutta (now Kolkata) to Demerara (now Guyana), The Hesperus, departed in May 1838. The vessel arrived in Demerara on May 5, 1838, with 156 Indian labourers onboard. This event is commemorated annually in Guyana as Indian Arrival Day. The roots of these three coincidental events could be traced to the same historical origin.

Although a Kenyan by birth, Ngũgĩ’s literary legacy is intertwined with the struggle for African identity and the history of preserving the cultural identity of the indentured Indian diaspora in the post-slavery era. Ngũgĩ was born in 1938, exactly a century after The Hesperus arrived in Demerara from India. Later, he became a leading voice of the post-colonial struggle in Africa.

Ngũgĩ was not only a powerful author, but also a symbol of the anti-colonial struggle. Born in a remote village in Kenya, he experienced the atrocities of colonial British rule and also witnessed the 1952 Mau Mau uprising. He realised that imperialists not only occupied foreign countries, but also hegemonised languages and thought processes of their peoples. The main purpose of celebrating African World Heritage Day is to preserve the cultural identity of people of African descent, apart from highlighting the vast cultural heritage of the African diaspora across the globe. Ngũgĩ portrayed the lifelong struggle of the Africans in his literary works, especially in his 1965 novel The River Between. In this novel, the Honia River acts as a potent symbol of division, not only separating the Gikuyu community of Kameno and Makuyu, but also reflecting the broader isolation experienced by colonised peoples worldwide. The physical presence of the river mirrors the ideological and cultural rifts caused by colonialism, highlighting the conflict between traditional Gikuyu practices and the influence of Western Christian missionaries.

One should not forget that many of those bonded labourers arrived in Eastern Africa, especially Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania, from India in the 19th Century. Although Ngũgĩ did not mention hardship faced by those Indian immigrants, the identity crisis and cultural conflict of a post-colonial society as described by the author have a striking resemblance to the events experienced by the Indian diaspora. In his Decolonising the Mind, he argued that the imposition of colonial languages, like English, on colonised populations serves to undermine their native cultures, identities and historical narratives, effectively “colonising the mind“.

Ngũgĩ wrote: “There is no death, there is only a journey from one bank to the other like a river.” It is basically a metaphorical expression, suggesting that death is not an end, but rather a transition, a change of state, similar to crossing a river from one side to another. The river itself symbolises the continuity of life and the ongoing cycle of change, while the two banks represent different stages or aspects of existence. This idea is central to the novel’s (The River Between) exploration of cultural identity, tradition and the impact of colonialism on the Gikuyu people of Kenya. One can find the recurring image of a riverbank in his writings. The Indians, who crossed the ocean in search for an uncertain future, secured their places in Ngũgĩ’s thoughts in a different manner. It seems that one of the banks is the Indo-Pacific, a vast maritime area encompassing the Indian and Pacific Oceans, and the countries and territories that border them. It includes parts of Africa, Asia, Australia and even the Americas. Interestingly, the Indo-Pacific unites the African and Asian diaspora. Hence, he wrote: “Language as culture is the collective memory bank of a people’s experience in history.”

The Gikuyu folklore, Chinua Achebe‘s ‘Things Fall Apart‘ and the anti-colonial psychological analysis of French West Indian political philosopher Frantz Omar Fanon (July 20, 1925 – December 6, 1961) highly influenced Ngũgĩ’s thought process. As an author, playwright and educator, he fostered an intercontinental dialogue. His legacy has spread beyond Africa, to other countries, like India, where discrimination on the basis of language, politics, geography, displacement, race, religion and caste still exists. His works remind one that colonial history is never over as state repression is not only an administrative failure, but also a manifestation of the pervasive trend of colonialism. Ngũgĩ fought against all these menaces throughout his life. The call for cultural resistance in his writings is relevant not only in the context of Africa, but also in the context of any other country in the contemporary world.

His Petals of Blood (2018) highlights the post-independence betrayals as new rulers carry the legacy of former colonial oppressors. While Ngũgĩ stressed on the cruelty of capitalism in his Devil on the Cross (1980), he raised questions about the boundaries between revolution and self-contradiction in A Grain of Wheat (1967). His works are actually a form of protest against the oppression of tribal and indigenous peoples, and also against the policy of suppression of the peasant movement.

Ngũgĩ never tolerated attacks on the Freedom of Expression. He repeatedly mentioned that culture (or freedom) is not a moment, but a continuous journey. The process moves forward when we save a lost language, publish forbidden verses or float down a river of memories with loved ones. One can easily find the everyday struggle of common people in colonial history.

Latest Release: Tegart’s War: A Story of Empire, Rebellion and Terror by Stuart Logie

Available on Amazon, Amazon India and Kindle

Boundless Ocean of Politics on Facebook

Boundless Ocean of Politics on Twitter

Boundless Ocean of Politics on Linkedin

Contact us: kousdas@gmail.com