The Child Of Sufferings

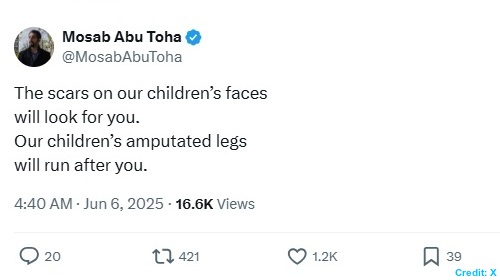

“The scars on our children’s faces/will look for you./Our children’s amputated legs/will run after you.” It seems that it is not just a verse, but a curse.

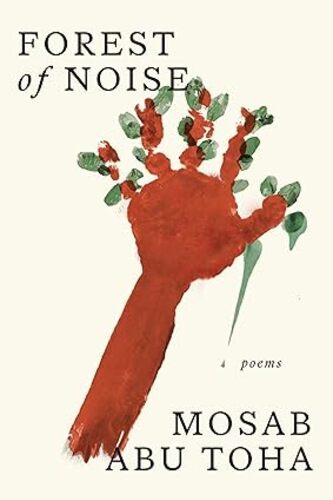

Mosab Abu Toha (b. November 17, 1992), the Palestinian writer, poet, scholar and librarian from the Gaza Strip, was born in the Al-Shati refugee camp shortly before the signing of the Oslo Accords. He recently won the 2025 Pulitzer Prize for Commentary for his portrayal of the Gaza War in The New Yorker. The Forest of Noise, his second collection of poems about life in Gaza, shows that a few lines can be more powerful than a live broadcast of the destruction of a city and dismembered bodies on television. Missiles coming down from the sky and explosions instantly turning high-rise buildings into dust create a bit of excitement in the mind of viewers who enjoy watching the game of war from a safe distance. However, poetry bridges that distance in a flash, helping readers to realise the condition of those who live in a war-ravaged territory.

Abu Toha’s poems introduce readers to his extended family, some of whom are no longer with him. In this context, one can mention his line: “I leave the door to my room open, so the words in my books/the titles, and names of authors and publishers/could flee when they hear the bombs.” (Under the Rubble, September 30, 2024) The basic characteristic of war poetry throughout the ages is to describe the destruction in a few simple words with an extraordinary impact. When the horror of reality surpasses imagination and the scale of destruction transcends human comprehension, the heart-rending lamentation remains as poetry. The works of Abu Toha are no exception. Noreen Masud of The Guardian has stressed: “If literature has any power to change the world or resist injustice, I think it must lie in the astounding poems of Mosab Abu Toha.”

The ancient Mesopotamian city of Ur experienced destruction and decline due to attacks, as well as conquests, by outsiders, primarily the Elamites and Amorites. The Lament for Ur, narrated by the Goddess Ningal, is a Sumerian poem composed around the time of the end of the city’s Third Dynasty (c. 2000 BC) that mourns the destruction of Ur. In this poem, Ningal expresses the grief and devastation caused by the city’s fall. The goddess describes the attack by the foreigners as the fury of a storm that destroys the sheepfold. According to historians, the destruction of the sheepfold actually symbolises the fall of the city. Although the Lament for Ur has been narrated mainly from the perspective of Ningal, other sections of this poem describe the desolation of the city.

Interestingly, all the major ancient epics stress on the importance of human relationships, amidst destruction, violence, death and sorrow. In Iliad, Priam, the elderly King of Troy, humbly begs Achilles for the body of his son, Hector (who was assassinated by Achilles). Priam’s act of supplication is a poignant moment in the epic, highlighting the grief, as well as desperation, of a father mourning his son and the complex emotions of the warrior (Achilles). Modern warfare has almost eliminated the space for human encounters and competition. It has also changed from large-scale clashes of Armies to suppression of civilian populations.

The poets shattered the romantic notion of war during the First World War. Wilfred Edward Salter Owen (March 18, 1893 – November 4, 1918), an English soldier who was also one of the leading poets of the First World War, portrayed the horrors of trenches and gas warfare in a different manner. His literary works stood in contrast to the public perception of war at that period of time and to the confidently patriotic verse written by earlier war poets, like Rupert Brooke. The description of soldiers “walking barefoot, hunched over like old beggars, coughing like old women, bloody feet, gasping for breath” is a powerful image from Owen’s poem Dulce et Decorum Est. This imagery portrays the harsh realities of trench warfare and the devastating physical, as well as mental, toll it takes on soldiers, contrasting sharply with romanticised notions of war.

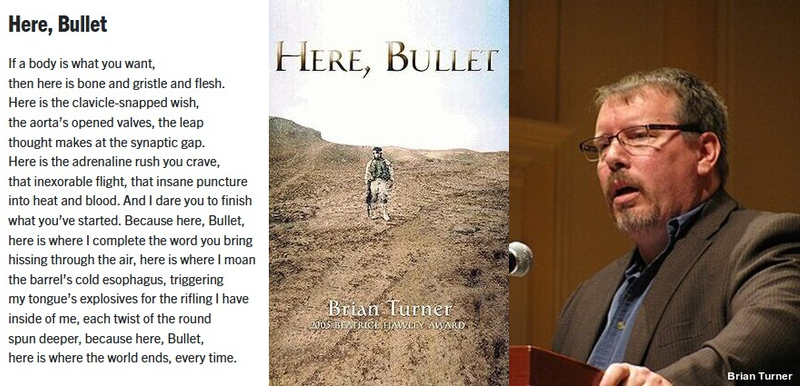

War poets are like military bloggers who present what is happening in the battlefield in a quite clear and concise manner. Brian Turner, the American poet, essayist and professor, showed the audacity to challenge the US’ decision to trigger the Iraq War in 2004, stressing: “Here, Bullet, here is where the world ends, every time.” (Here, Bullet) It may be noted that he won the 2005 Beatrice Hawley Award for his debut collection, Here, Bullet. It was the first of many awards and honours Turner received for this collection of poems about his experience as a soldier in the Iraq War.

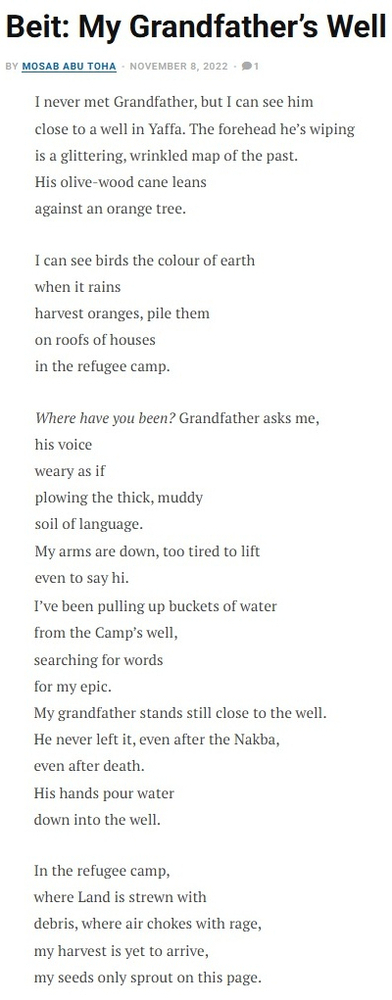

War cannot kill a poet. Just like crops, words, too, start from a seed, developing roots and shoots (sprouting), and eventually producing new seeds. Hence, Abu Toha wrote: “I’ve been pulling up buckets of water/from the Camp’s well,/searching for words/for my epic.” (Beit: My Grandfather’s Well; 2022)

Palestine is lucky enough to have a son, like Abu Toha, a graduate in English Literature who presents the life of a writer navigating the space between two opposing fronts in his own style.

Boundless Ocean of Politics on Facebook

Boundless Ocean of Politics on Twitter

Boundless Ocean of Politics on Linkedin

Contact us: kousdas@gmail.com