Charles Tegart & The Imperial Boomerang

By Stuart Logie

Part One: Information And Power

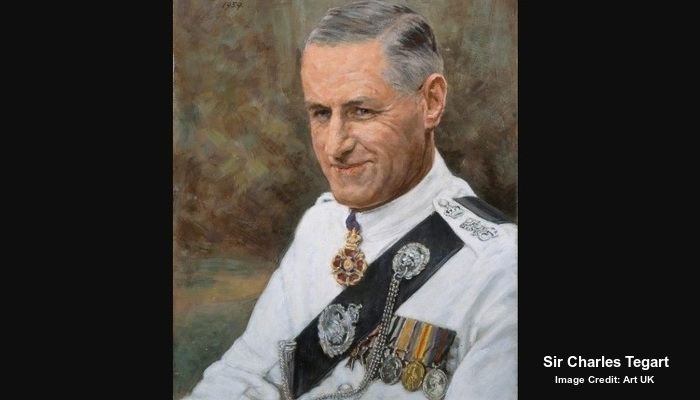

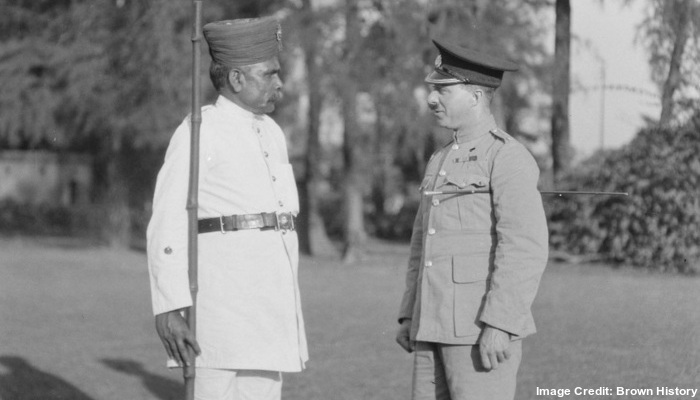

When I began researching the life of Sir Charles Augustus Tegart (October 5, 1881 – April 6, 1946), a British colonial policeman who had worked in India, Ireland, Mandatory Palestine and London from 1901-1945, I had no notion of the thesis, called the Imperial Boomerang. Yet as I progressed with my research, I had a hunch that at least I might find Tegart’s colonial legacy in today’s institutions responsible for public and national security.

Tegart arrived in India in 1901 just when the modern techniques of policing were emerging and a nationalist rebellion was taking root. These two events occurred, not in a liberal democratic metropolis, but in an autocratic colonial state that had become a laboratory for experimentations in policing not yet seen anywhere else in the world.

The young Tegart found himself in the new realm of political policing. Shrouded in secrecy by the first official secrets act, political policing consisted of surveillance and countersurveillance, new technology, spies and informants, witness relocation, signal intercepts, secret renditions and black operations, interrogations with systemic torture, preventative policing and administrative detention, remote prisons and secret detention houses, all of which had become the hallmarks of the state war on terror we are familiar with today.

Tegart also had a very important colonial policing mentor whose work heavily influenced the arc of his career with the colonial police.

The Innovations Of Col. Ramsay

In the history of policing, the establishment of the London Metropolitan Police by Sir Robert Peel in 1829 is seen as the watershed moment in modern policing. It was also a time of empire, so whatever was developed in the metropole for modern policing would evolve down in some bastardised version to the colonies with their own special needs.

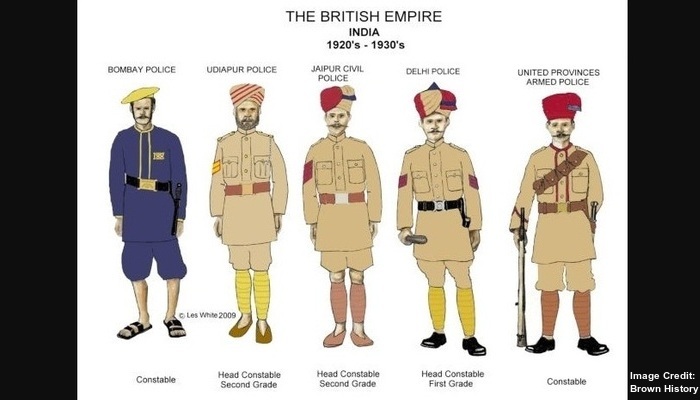

In fact, colonial policing by its very nature was different from policing in the metropole. For one thing, they policed people who did not yet embrace liberal democracy and the rule of law. It was a rougher sort of policing intended to subdue an uncivilised people, and it relied on a heavy dose of metropole policing techniques, such as whipping and transportation of convicts, to the ends of the empire.

But while colonial policing did share some tactics and strategies typical of the metropole, there were also many innovations in colonial policing that would eventually find their way back to the metropole – and this is what I later discovered to be the imperial boomerang. The most important of these innovations was the treatment of information and the new power it gave to the Police.

Bengal was the beating economic heart of Colonial India, a vast machine of wealth extraction that generated reams of information. Colonial policing, meanwhile, was not so adept at information gathering and processing. For instance, colonial detectives traditionally collected information that they retained personally and then destroyed when they retired. In Bengal, that changed with the work of Patna Police Superintendent Colonel H M Ramsay between 1874-1881.

Ramsay recognised the importance of information in policing. He understood that if you could gather, organise and distribute information, there were benefits not only in the prevention of crime, but also in a reduction in police corruption and laziness. Ramsay’s new techniques, described in his book Detective Footprints, became the longest serving codification of Police knowledge in the common law world.

Imagine, if you will, a pile of bills of sale: it simply lists items with a total. At that time, this was essentially the Police crime reporting system, just a list of crimes and the Police response. There was little or no context. Now, imagine a ledger. You would have sales information, purchase information and general information, with an opening or brought-forward balance. That was the kind of Police crime reporting system the superintendent wanted to see. It would give senior Police officers a whole new view, not only of crime and criminals, but also the performance of their own Police subordinates.

Ramsay’s innovations did not immediately reverberate in the metropole for a simple reason: his system depended on a high degree of invasive Police surveillance, informers and spies, and other tactics of information gathering that would not have been tolerated in the Victorian metropole. However, they were perfect for colonial Bengal and they became the foundation of modern preventative policing in the colonial context. They also formed a key part of the imperial boomerang.

Charles Tegart & The Special Branch

Twenty-year-old Charles Tegart was a polo-playing, Irish college student when the British Imperial Police recruited him to serve in India in 1901. His first posting was as Police Chief in the Bengali city of Patna where he was introduced to Ramsay’s system for information gathering.

At about this time, an Indian Government Police Commission had come down hard on the inefficiency and corruption within the Indian Police, with the possible exception of Bengal. Even though Bengali Police were poor performers in many respects, they did have some hope in the success of the Ramsay system of preventative policing. Tegart became a champion of reform based on Ramsay’s system within the Patna Police, and later at three other posts, most notably his posting to Calcutta (now Kolkata), the largest City Police Force in the country.

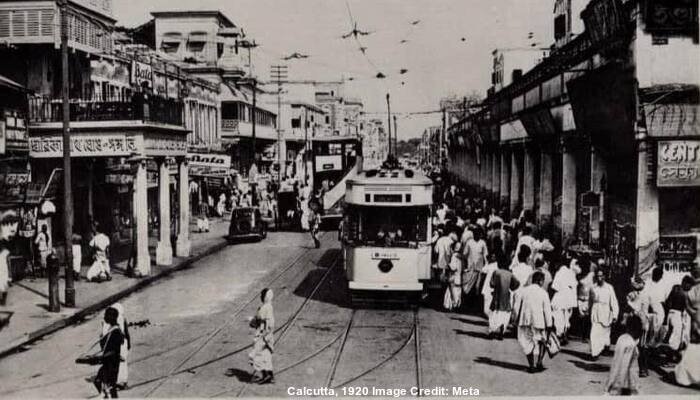

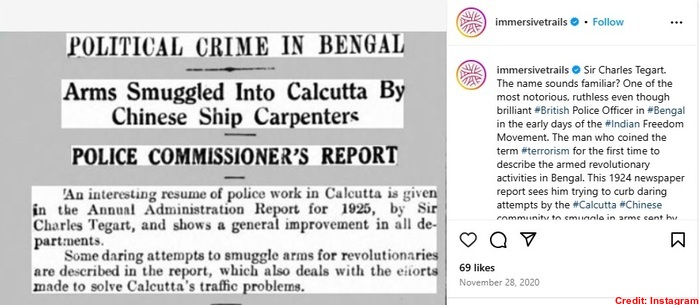

With the Calcutta posting, Tegart had arrived at the right place at the right time. Calcutta was already a source of policing innovations; a system of fingerprints was invented there, and Police photography for “mug shots” was widely used. Calcutta was also the nexus of political unrest that attracted extremists from all over Bengal and the rest of India. At first, they were considered lone-wolf anarchists. But as they evolved into highly organised and efficient gangs dedicated to violence, they came to be referred to as terrorists. Tegart and his newly created Special Branch for political crime investigation led the repression of the rebellion, using Ramsay’s techniques for surveillance and information gathering. Even with this though, Tegart encountered judicial obstacles in his pursuit of the terrorists.

The Empire had already acquired previous experiences with such violent, organised gangs: the pirates who threatened their imperial trading routes and the Indian thugs who robbed and strangled travellers. In the eyes of the Empire, these brigands operated “beyond the pale” of law and norms of civilised society. Thus, colonial authorities dealt with them by issuing temporary ordinances which deprived these pirates and thugs of the due process of law. It was colonial executive power at its most naked. Tegart later found out he needed such power to eradicate the current terrorist threat. The exceptional power granted by such ordinances became Tegart’s go-to tool against the Bengali terrorists.

Without such powers, Tegart felt strongly that the system of justice was incompatible with his mission to eradicate terrorists. His formidable network of informants was useless if he had to go through due process, as no one would step forward as crown witness. It only worked if he had the exceptional power to arrest and detain for an unlimited period of time, or until he had eradicated the threat. Wherever Tegart came in touch with law-makers, he argued that counterterrorism did not work if you have to produce evidence for judicial scrutiny.

A determined and often ruthless Tegart took the government to the dark side of counterterrorism. He manipulated the courts with planted evidence and deceits. He believed in torture and interrogation over patient investigation. And, he championed the use of ordinances to fight the terrorists who operated “beyond the pale”. His goal was urgent: the complete eradication of the terrorist network, at any cost. Over time, he convinced lawmakers to treat terrorism with permanent counterterrorism measures, such as the Rowlatt Act, to be drawn down when needed.

Apart from the law, there were many police innovations during Tegart’s term in Calcutta. Working with the Army signals group, he developed a sophisticated system of intercept. It was so good the extremists had to place a single strand of hair in every missive; if it was missing, then the missive had been intercepted. That’s how good the intercept was. (Police did figure out the hair trick and left it in place.) Tegart also understood the importance of financial tracking, i.e., following the terrorist money.

On the subject of torture, Tegart had a certain reputation. But one must remember that the use of torture to gain criminal confessions is as old as crime itself. The Indian Police had always had a complicated relationship with torture (the term third degree comes from the Indian Police). What Tegart did was to normalise torture in the Police culture by organising it a better way and making it more efficient and less visible. The purpose of interrogation was to obtain information, not just a confession. Torture was performed mainly by practiced interrogators; lower-level policemen were no longer allowed to carry out confession-seeking torture sessions on their own.

Near the end of his posting in India, the Bengali rebellion took a turn for the worst and for the first time in a long while the military had to be called in. At this point, there began a militarisation of the Police in a situation where Army counterinsurgency meets Police counterterrorism.

Part Two: The First Terrorism Expert

So far, we have seen how the colonial context provided a laboratory for the development of tactics and strategies in the new Police practice of counterterrorism. We see this through the eyes of one of its leading architects, Policeman Charles Tegart. Now, we look at the directionality of the imperial boomerang: How did it go from a rebellion in Bengal into the broader context of the colonial metropole, the control centre of the Empire, that made counterterrorism a global practice?

Using the extraordinary powers of the Defence of India Act during the First World War, Tegart succeeded in smashing the rebellion in Bengal in 1917. However, he did not eradicate it. Indeed, many rebels fled the country to continue the rebellion from where they sought the support of Britain’s enemy, Germany, and later Russia. Thus, the rebellion became a global issue for the Imperial Police and it needed experts who could operate in this new dimension of counterterrorism. Charles Tegart was its leading expert in this rebellion, and so in 1917, he was transferred to London to become the Deputy Director of the shadowy India Political Intelligence (IPI) Bureau where he worked until 1923.

Tegart was really just one among many Imperial Police officers working in this regard. Tegart’s Indian Police colleagues Godfrey Denham and David Petrie (who later would become the Wartime Director of MI5) supplied him with intelligence inputs from the far-flung corners of the Empire on the international movement of Indian revolutionaries, arms shipments, financial transactions and propaganda materials. There was even an attempt by Denham to execute an extraordinary rendition of a wanted Indian terrorist in Mexico. However, Tegart, unlike his colleagues, was based in London where he actively influenced the views of the leading political decision-makers in the Empire. This influence cannot be underestimated particularly given the forceful personal nature of the man and his absolute devotion to eradicating terrorism.

The Police View

When the war ended and Britain came to terms with its new adversary Russia, Tegart was returned to India to be the Police Commissioner of Calcutta where the terrorists were once again gaining the upper hand. This time though Tegart was a much more formidable adversary. He had established relationships with the top decision-makers in London, including Victor Lytton who was Parliamentary Undersecretary to the India Office when Tegart was at IPI, and later became the Governor of Bengal when Tegart was Police Commissioner. Their friendship allowed Tegart to create the largest intelligence gathering operation in the Empire, and to virtually direct the counterterrorism efforts across Bengal.

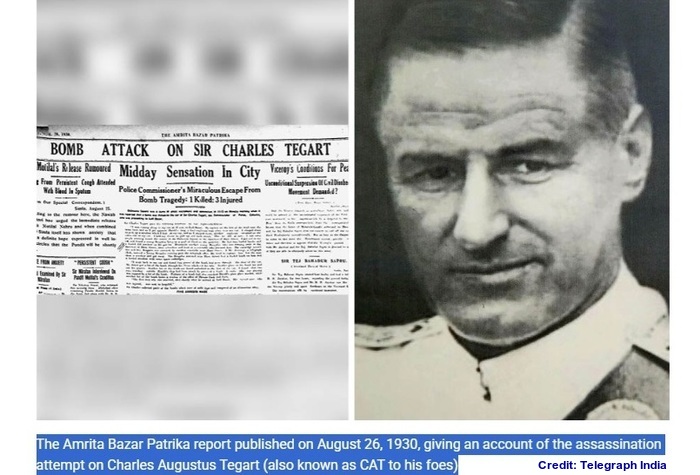

While some decision-makers in London felt it was sometimes necessary to “rise above the police view”, they did so at their own risk. When the terrorists attacked the Chittagong armoury and the Calcutta Government offices in the Writers Building in 1930, suddenly the Police view was more important than ever. After an assassination attempt that nearly succeeded, Tegart was returned to London where the “police view” now became a fixture in the India Office.

Tegart worked closely with the India Office for the next several years to develop global strategies in order to combat the terrorist movement. He gave advice to Governor of Bengal John Anderson, another top government official he knew personally from London. He gave lectures on his experience in counterterrorism and prepared a report that detailed the scale of his counterterrorism activities in Bengal, all of which suited the needs of the India Office. The Secretary of State for India was negotiating with leading political figures (including Mahatma Gandhi) and Tegart represented a big stick to go along with the carrots of negotiations. It was the first instance of where the Police (and not the military) were used as a negotiating tool to stem the slide into decolonisation.

In 1935, the Secretary of State for India negotiated a deal with the Indian political leaders and Tegart’s role as a counterterrorism expert in India came to an end. It was not, however, the end of Tegart’s career in counterterrorism. His next assignment would leave a lasting legacy and solidify his reputation as the leading counterterrorism expert for the state.

The Arab Rebellion

In 1936. a rebellion broke out in Mandatory Palestine, a relic of the Ottoman Empire. Britain had a mandate to control the region since shortly after the First World War when the League of Nations gave it the mandate to prepare Palestine for statehood. But the incipient state had a wrinkle, called the Balfour Declaration, which called for the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people. By 1936, the Arabs of Palestine were in full revolt against the British and the Jews.

The British sent in the military to pacify the rebellion in the largest movement of troops since the Great War. The British also had a long-term vision of state security that would depend on the role of the Police. For that, they turned to their terrorism expert, Charles Tegart, for advice.

Tegart was offered the post of Director of the Palestine Police, but he turned it down. In his mind, the days of pitched battles with terrorists were behind him. He was now in a position to shape government policy given his personal connections at the highest levels of the state. A new state was being created and he saw an opportunity to shape a new kind of Police force based on his experiences in Colonial India. It is a tangible example of the imperial boomerang.

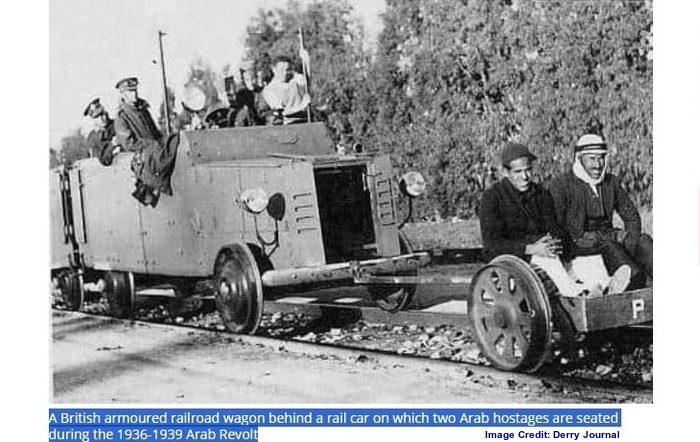

But first Tegart needed to work with the military to subdue the rebellion. Tegart drew on his expertise from India when he had collaborated with John Anderson, the Governor of Bengal, who was overseeing the first concerted militarisation of the Police in Bengal. After the Chittagong armoury raid, the military and the Police conducted cordon and search operations to track down the terrorists: the military would cordon off an area known to harbour terrorists, and then the Police would conduct the actual searches.

When this failed to produce intelligence results, the military supplemented the ranks of the Bengal Intelligence Branch Police with Military Intelligence Officers (MIOs). This new intelligence effort was bolstered by the Bengal Suppression of Terrorism Outrages Act, which imposed collective fines on villages found to have harboured terrorist subjects.

Almost immediately the flow of intelligence improved and the counterterrorism tactic of “good village and bad village” was born. It was a shining moment for the military, less so for the Police. The presence of the military changed the nature of Police areas of information gathering, interrogations and investigations, and marked an important turning point in the militarisation of the Police. It was counterterrorism at a new level of violence.

Later in Palestine, Tegart worked as a liaison between the Police and the military. In a public security meeting, Tegart proposed the “good village-bad village” strategy of population-centric pacification. The result of these village-based punitive actions was a dramatic increase in Palestinian and Jewish collaboration with the military and Police intelligence, just like what happened in Bengal.

Tegart’s mandate remained Police-focused in this newly militarised zone of policing. Yet at the same time, he had to respond to the military who were ultimately responsible for all the public security and counterterrorism; they would someday soon hand over complete public security to the Police. Before that could happen, and Tegart heard this from Major General Bernard Montgomery, the same who famously advised the Palestinian Police to shoot men with hands in their pockets, the Police needed a more accommodating and militarised base to provide public security. Security of the Police first, and then security of the public. So was born Tegart’s forts.

You may also like: Colonial India’s ‘Counterterrorism Expert’ In Palestine!

Technically, Palestine was not a colony. But it was nonetheless in the process of decolonisation and all that it entails, including the notion of a colonial boomerang. Tegart’s forts are a reminder that the tactics and strategies of the Colonial Police to suppress terrorism still play a role in the modern liberal democratic state where they reside – Israel.

But that’s another story in the Imperial Boomerang Thesis.

Boundless Ocean of Politics has received this article from Stuart Logie. Mr Logie is a former Montreal-based journalist and a corporate executive. He is also the author of Winging It – The Making of the Canadair Challenger. The Aviation and Space Writers Association honoured his work with the Book of the Year award. Mr Logie has also penned a book on the Canadian aircraft programme and several articles on the emerging technology industry. He lives in Montreal and also in Italy.

The book, Tegart’s War: The untold story of a colonial policeman, three rebellions, and the beginnings of the war on terrorism, will be published soon. Follow @TegartsWar on X (formerly Twitter) for updates.

Latest Release: Tegart’s War: A Story of Empire, Rebellion and Terror by Stuart Logie

Available on Amazon, Amazon India and Kindle

Boundless Ocean of Politics on Facebook

Boundless Ocean of Politics on Twitter

Boundless Ocean of Politics on Linkedin

Contact: kousdas@gmail.com

1 Comment »