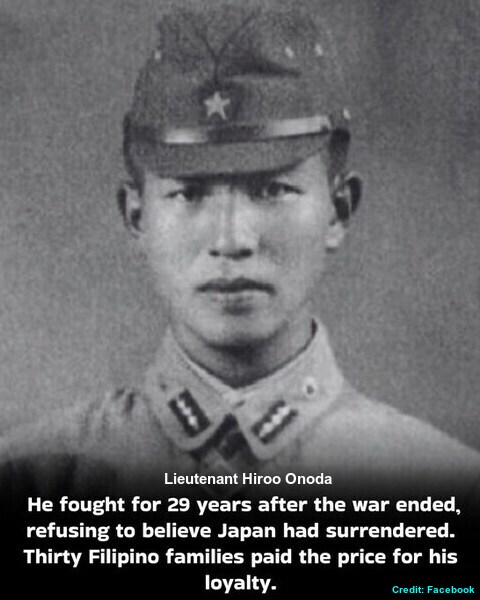

A Loyal Soldier Who Never Surrendered

He fought for 29 years after the war ended, refusing to believe Japan had surrendered, and 30 Filipino families paid a heavy price for his loyalty.

In December 1944, the 22-year-old Lieutenant Hiroo Onoda received orders that would define the rest of his life: Conduct guerrilla warfare on Lubang Island in the Philippines. Do not surrender. Do not commit suicide. Fight until relieved of duty by a superior officer. Onoda took those orders quite seriously.

By March 1945, the Allied Forces had captured Lubang Island and destroyed the Japanese garrison. All that remained were Onoda and three enlisted men, who retreated into the mountains to continue their mission. On August 15, 1945, Japan surrendered as the Second World War was over. However, Onoda did not believe it.

American aircraft dropped leaflets over the mountains in Japanese language, announcing the surrender. Onoda examined them and concluded that they were Allied propaganda, a trick to make him surrender. More leaflets came and those included a direct order from the Japanese general who had commanded forces on Lubang Island. Surrender. The war is over. Come down. Onoda analysed the leaflets carefully. The syntax seemed wrong and the paper quality was suspicious. Conclusion: Forgeries. The war continued.

By 1950, one of Onoda’s comrades broke away and surrendered on his own, leaving three others on the island. Photographs of his surrender surfaced, along with letters from families, with parents begging their sons to come home as the war was over. Onoda and his remaining two companions studied the letters, but came to the conclusion that it was part of a sophisticated psychological warfare. They thought the enemy had captured their families and forced them to write. Hence, they decided not to fall for tricks.

In 1954, one of Onoda’s comrades was killed in a firefight with a Philippine Army patrol, leaving only two. For the next 18 years, Onoda and Kinshichi Kozuka lived in the jungle, emerging periodically to raid rice stores, steal supplies and continue their guerrilla mission.

Here’s what the story usually skips: The civilian cost. Filipino farmers were trying to work their fields in villages on Lubang Island. People who had nothing to do with the Second World War, except the misfortune of living where Onoda had decided to keep fighting.

Over 29 years, Onoda and his fellow Japanese soldiers killed approximately 30 Filipino civilians, including farmers and villagers, even after the end of the war. Each death was tactical to Onoda as it was a necessary action for him. To the families, they were murderers.

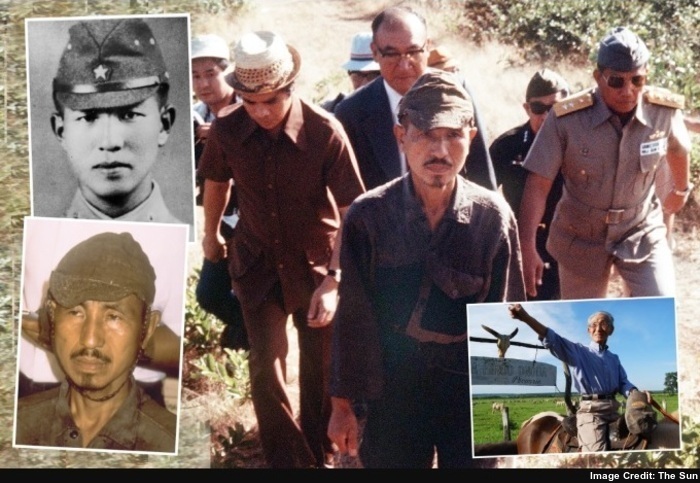

In 1972, Kozuka was killed by the Police during a rice raid, leaving Onoda alone. For two more years, a single Japanese officer in tattered uniform continued guerrilla operations on Lubang Island, still convinced the Second World War was ongoing and still following orders from 1944. In February 1974, a Japanese adventurer, named Norio Suzuki, hiked into the mountains specifically to find Onoda. After days of searching, he located him. Suzuki tried to convince Onoda that the war had ended long ago. However, Onoda refused to believe it. He told Suzuki that he would only surrender if ordered to do so by Major Yoshimi Taniguchi, the officer who had given him his original orders in 1944.

Suzuki returned to Japan, found Taniguchi (now a bookseller) and convinced him to visit Lubang Island. On March 9, 1974, Major Taniguchi stood before Lieutenant Onoda in the jungle and formally relieved him of duty, saying that the war was over and his mission was complete. After 29 years, Hiroo Onoda surrendered and returned to Japan as an unwilling celebrity. The media treated him like a hero, the last soldier, unbending in loyalty, faithful to his orders for three decades.

The Government of the Philippines, under President Ferdinand Emmanuel Edralin Marcos Sr, pardoned Onoda for the killings. However, back on Lubang Island, the residents were not celebrating. Thirty families had lost their loved ones, while others had been injured. For 29 years, they had lived in fear of a Japanese soldier who refused to believe the war had ended. Onoda was getting away with murder, literally.

Onoda never acknowledged the civilian deaths in his bestselling autobiography. He refused all demands for compensation from victims’ families. He criticised what he saw as Japan’s cultural decline, accepted no back pay from the government and moved to Brazil in 1975 to become a cattle rancher.

Onoda founded a nature school in 1984, teaching Japanese children outdoor survival skills. He also became a motivational speaker about duty, as well as loyalty. He never apologised to the families on Lubang Island.

Hiroo Onoda died on January 16, 2014 at the age of 91 in Tokyo. He was eulogised as a symbol of unwavering dedication. But dedication to what? Orders from his senior to fight a war that had ended 29 years before he finally surrendered? Loyalty that killed 30 innocent people? There is something to be said for following orders, for commitment, for loyalty even in impossible circumstances. There is also something to be said for questioning whether one is fighting the right war… for recognising when circumstances have changed, for considering the cost her/his mission is inflicting on innocent people. Onoda followed his orders perfectly. He never surrendered and never gave up. And 30 Filipino civilians died because of it.

That is not a story about his heroic dedication. That is a story about what happens when loyalty becomes detached from reality. When following orders matters more than questioning whether those orders still make sense. The families on Lubang Island did not want a hero’s story. They wanted accountability for their murdered loved ones. They never got it.

Hiroo Onoda spent 29 years fighting a war that had ended decades ago. He survived and became famous. He lived to 91. The members of 30 families killed by Onoda and his comrades did not survive. They do not have autobiographies and nature schools named after them. They just have graves and families who were told to forgive because the man who killed their loved ones was just following orders.

Loyalty is admirable. Dedication is valuable. Following orders has its place. But so does knowing when to stop. So does recognising reality. So does being held accountable when one’s actions kill innocent people. Hiroo Onoda would be remembered as the soldier who did not surrender. The 30 civilians on Lubang Island would be remembered only by their families, if at all. That is the real story.

Collected from the Facebook page of The Inspireist’s Post.

Meanwhile,

Boundless Ocean of Politics on Facebook

Boundless Ocean of Politics on Twitter

Boundless Ocean of Politics on Linkedin

Contact us: kousdas@gmail.com