Let’s Recover The Lost Meanings Of Republic

Let’s recover the lost meanings of Ganarajya to face the political challenge of our time

by Yogendra Yadav

Ganarajya (Republic) or ganatantra (Democracy)? Our passport and the Indian Constitution name our republic as ganarajya. But our Republic Day is officially called Ganatantra Divas. A small discrepancy, you might think. Perhaps an oversight. Or, maybe a nuance. That is what my publisher thought, when I pressed him to change the title of my recent book from the proposed Ganatantra ka Swadharm to Ganarajya ka Swadharm.

This seemingly minor difference invites us to search deeper. These two terms allow us to distinguish between two different concepts for which the English language has just one word – “Republic”. Once we extricate the concept of ganarajya from the more familiar and dominant concept of ganatantra, it opens the way to recovering the lost meanings embedded deep in the idea of a ganarajya. This recovery, in turn, sets us on a path to face the political challenge of our times.

I am not suggesting that one of the two usages is wrong. Unlike these days, the makers of our Constitution and the early guardians of our republic were very careful with their words. They must have had good reasons to call it “Ganatantra Diwas” and not “Ganarajya Diwas”. I am not saying that one of these words is more authentic. Sanskrit scholars tell us that both these words are pretty recent, 19th- or 20th-Century, coinages. The “republics” in ancient India were called “gana” or “sangha”, not “ganarajya” or “ganatantra”. Nor do I claim a direct link between these words and the historical reality of ancient Indian ganas (people). Historians warn us against comparing these older political formations with modern democratic republics. The polities of Vaishali or Lichchhavi are best described as lineage-based oligarchies rather than democracies in our sense of the term. My point here is to underline the distinctiveness of these two terms and uncover their different political possibilities.

Ganatantra refers to a negative and very narrow meaning of a republic. Political Science textbooks tell us that a republic is a form of government where the Head of State is not hereditary. Britain is ruled by a king, so it is not a republic. Nepal has done away with the king, so it is now a republic. This is simple and clear-cut. But it also renders the idea pretty much useless. Except for a handful of titular monarchies, virtually every country – democratic or otherwise – is a republic these days. An adjective that applies to nearly everyone is redundant. So is this concept of the republic. That is why students of Political Science do not use this concept in any meaningful way. We learn about it in our textbooks and forget about it.

Sometimes, ganatantra is used in a broader sense. It is used not just negatively to refer to the absence of monarchy but also positively to refer to the mechanism of popular sovereignty, the tantra of gana (system run by the people). Thus, it means the institutional structure of electoral democracy through which popular sovereignty is exercised. In this broader usage, ganatantra is a near synonym of lokatantra or electoral democracy. Here again, ganatantra is repetitive and superfluous. No wonder ganatantra is a decorative expression that does very little in our political imagination.

Ganarajya takes us to deeper and positive meanings embedded in the idea of a republic. Here, the republic is a normative political order. The public is not just a collection; it is a community of equals. This community evolves its own norms, its distinct dharma. These norms are upheld by inculcating civic virtues. The people enforce these norms by holding the rulers accountable. The people are not just the source of power; they are also a check on power. In the European tradition, “republicanism” stood for this radical meaning of republic. In recent years, academic revival of “republicanism” in Western Political Theory has defined a republic not just as absence of monarchy but as absence of domination of any kind.

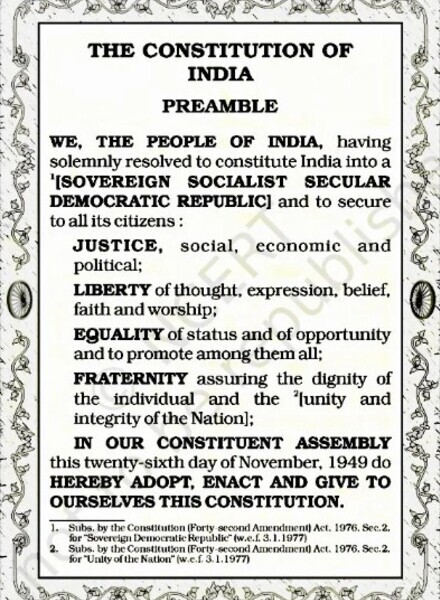

This radical concept of a republic is very much the republican idea upheld by the Indian National Movement. The ancient Pali expression “samanna-rajya”, a polity where sovereignty is shared by equals, is close to this. In modern usage “Jan-Gan-Man” captures the spirit of our ganarajya. “Jan” stands for the people, the fountain head of sovereignty. “Gan” requires the people to be a political community where everyone exercises equal decision-making power. “Man” is about the collective conscience. It is not mere public opinion at any given point of time, but the ethical ideas that the public upholds on deeper reflection. A radical republicanism informs the Indian Constitution.

Understanding this Indian concept of republic leads us to a question: What are the ethical ideals that inform the Bharat ganarajya? One could turn to the Preamble of the Constitution to unpack these ideals. But this may not work at a time when the Constitution itself is under assault. We have to go deeper and ask: Why must we believe in these constitutional values? An answer to this would take us beyond the Constituent Assembly. For our Constitution was not written in two years; the ideas that went into its making were forged over at least 100 years. It would take us beyond the freedom struggle, as the national movement was not just a movement to liberate the country from British colonial rule. It was also a movement for the reconstruction of India. It was an encounter between our civilisational heritage and Western modernity.

A search for the ethical ideals embedded in the idea of ganarajya invites us to uncover the swadharm (character) of our republic. This is what the oft-quoted phrase “the idea of India” must mean. And that would lead us to a stark conclusion: What we confront today is not just a backsliding of our democracy, not just a mutilation of our Constitution. We face nothing short of a determined onslaught on the swadharm of our ganarajya. Defining and defending this swadharm must be our collective Republic Day resolve.

Boundless Ocean of Politics has received this article, published in The Indian Express on January 27, 2026, from Yogendra Yadav, the author of Ganarajya ka Swadharm (Setu Prakashan, 2026). He is a member of Swaraj India and the National Convenor of Bharat Jodo Abhiyaan.

Meanwhile,

Boundless Ocean of Politics on Facebook

Boundless Ocean of Politics on Twitter

Boundless Ocean of Politics on Linkedin

Contact us: kousdas@gmail.com