On The ‘Queen Of Curves’

A 63-year-old beautiful Iraqi lady, along with her co-passengers, was onboard an aircraft in September 2013, as the plane was all set to leave for Frankfurt. The pilot suddenly encountered a technical issue just before taking the aircraft to the runway from the parking bay. The cabin crews asked passengers for time to make repairs in order to ensure everyone’s safety as it is a standard procedure to allow mechanics to fix a problem. After a while, the lady lost patience as she had to attend a seminar in Frankfurt.

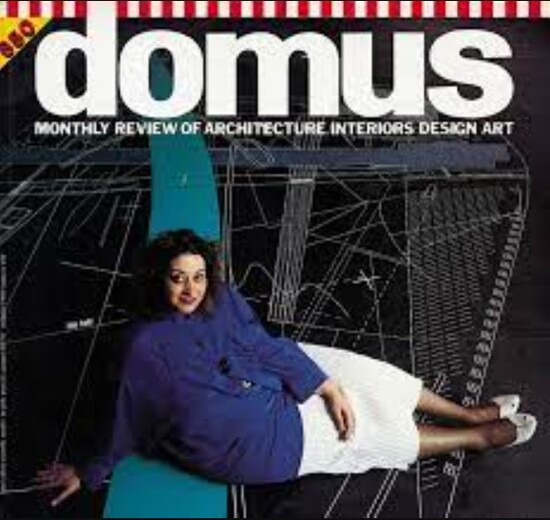

The flight attendants tried their best to convince her that it would not take long. However, the lady asked them to arrange a replacement flight for her. As they got involved in a verbal spat, one of the flight attendants noticed the cover of the latest edition of their in-flight magazine. There was an image of that lady on the cover of the magazine, as the lead story was about her!

The flight attendant, in a trembling voice, asked the lady: “Are you Zaha Hadid?” There was a pin drop silence inside the aircraft for a moment upon hearing her reply. Everyone heard the name of Dame Zaha Mohammad Hadid (October 31, 1950 – March 31, 2016), but nobody had ever seen her. Hadid, the Iraqi-born British architect, artist, designer and a key figure in the architecture of the late-20th and early-21st Centuries, is popularly known as the Queen of Curves. She became the first woman to receive the Pritzker Architecture Prize, one of the world’s premier architecture prizes which is often referred to as the Nobel Prize in architecture, at the age of 54 in 2004. The situation changed abruptly soon after she disclosed her identity and arrangements were made for a replacement flight.

Once, Rowan Moore, the renowned British architecture critic, narrated this incident in The Guardian. Interestingly, he was Hadid’s interlocutor at that international seminar in Frankfurt. There are many such incidents related to her that sound like fairy tales. Initially, she had struggled a lot to establish herself in a profession that has always been dominated by men. Early in her career, nearly 70% of her designs were rejected due to the reason that they were not technically feasible to build. However, Hadid emerged as one of the world’s leading architects by challenging every practical limitation and opposing the conventional forms, as well as dimensions, of architecture.

Hadid was born on October 31, 1950 in Baghdad to an upper-class Iraqi family. Her father, Muhammad al-Hajj Husayn Hadid, was a wealthy industrialist from Mosul who used to travel to different places with his little daughter. While Hadid’s mother, Wajiha al-Sabunji, was an artist from Mosul, her brother, Foulath Hadid (March 7, 1937 – September 29, 2012), was a writer, accountant and expert on Arab affairs. She studied mathematics at the American University of Beirut before moving to London in 1972 to study at the Architectural Association School of Architecture.

Hadid’s former Professor Rem Koolhaas described her as “a planet in her own orbit” and also as the most outstanding pupil he ever taught. Professor Koolhaas, a Dutch architect, stressed: “We called her the inventor of the 89 degrees. Nothing was ever at 90 degrees. She had spectacular vision. All the buildings were exploding into tiny little pieces.” He claimed that Hadid was less interested in details, such as staircases, stating: “The way she drew a staircase you would smash your head against the ceiling, and the space was reducing and reducing, and you would end up in the upper corner of the ceiling. She could not care about tiny details. Her mind was on the broader picture – when it came to the joinery, she knew we could fix that later. She was right.“

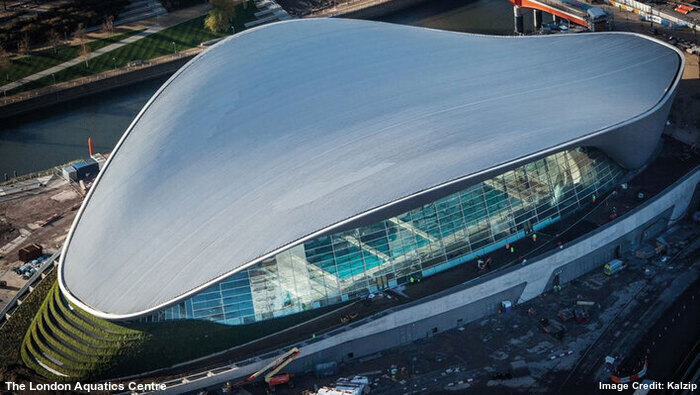

As a child, Hadid went on trips with her father to visit the ancient Sumerian cities in southern Iraq and those trips inspired her to become an architect. She recalled that the experience of seeing the landscape where “sand, water, reeds, birds, buildings and people all somehow flowed together” was a powerful and lasting memory. Her architecture is renowned for a rhythmic coexistence of asymmetrical, fluid, and dynamic shapes and volumes which brought her worldwide fame and earned the nickname Queen of the Curves. Her designs famously avoided right angles, instead employing sweeping, sinuous lines and forms that create a sense of movement and seamlessness. Hadid’s works are characterised by sharp angles, fragmented geometries and non-rectilinear shapes which appear to distort, as well as dislocate, traditional architectural elements, creating a dynamic and unconventional appearance. Many of her projects use cantilevers and design elements that make the structures appear to float or break free from the ground, challenging traditional notions of support and stability. Interestingly, Hadid’s buildings often seem to emerge from or flow into the surrounding landscape, blurring the lines between architecture and nature.

The rise of Hadid was not a smooth one as she had to face various obstacles. It may be noted that the Theory of Deconstruction, pioneered by French Philosopher Jacques Derrida (born Jackie Élie Derrida; July 15, 1930 – October 9, 2004) and considered a fundamental element of Postmodernism, had a significant impact on the architectural structures, as well as various branches of art and literature, at that period of time. Based on the idea of Deconstruction, the Post-modern architectural style, known as Deconstructivism, emerged.

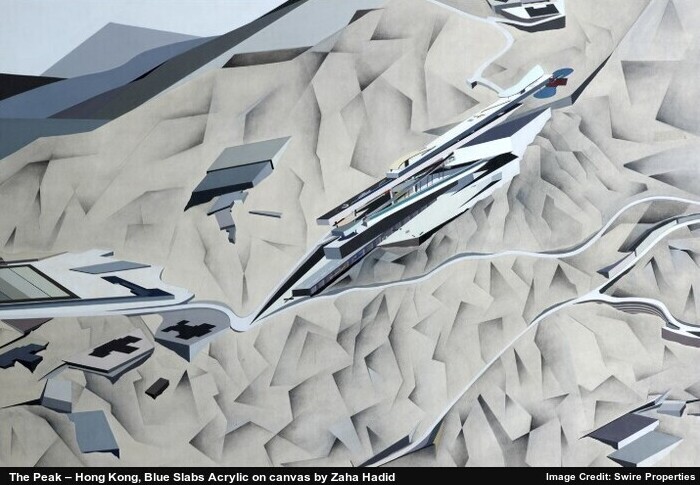

In the early days of her career, Hadid was greatly inspired by Russian painter Kazimir Severinovich Malevich (February 23 (O.S. February 11, 1879 – May 15, 1935) and his Suprematist Movement, which encouraged her to use abstraction and geometric shapes as a design tool for her architectural concepts, thus developing a new architectural language which moved beyond traditional, objective forms. This influence is visible in her early, often unbuilt, projects, like The Peak (1983). In Suprematism, various geometric shapes are placed at different angles with minimal use of colour, creating a scene that evokes a pure artistic feeling and a higher spiritual consciousness beyond the material world.

Although Hadid successfully blended Post-modern designs with pure artistic feeling, most of her radical architectural designs in the 1980s were never built, as they were considered too avant-garde and technologically challenging for their time. She was known as a Paper Architect during this period as her visionary concepts rarely moved beyond the drawing phase.

Hadid opened her own architectural firm, Zaha Hadid Architects, in London in 1980. However, she implemented her first major project, the Vitra Fire Station, in 1993 in Weil am Rhein, Germany. The fire station is famous for its sharp, angular and dynamic forms which are characteristic of her Deconstructivist style and represent a frozen explosion of the Suprematist Movement. The structure looks like a flying bird from a distance. The angular shapes and tilted walls of the fire station connect to and define the surrounding surface and landscape of the Vitra Campus.

This particular project established Hadid’s reputation and put her on the global map as a noted architect as her design attracted the global community. The Lois and Richard Rosenthal Centre for Contemporary Art in Cincinnati, Ohio, was built between 2000 and 2003. It was her first project in the US. Hadid designed the two distinct street-facing facades of this non-collecting museum on the basis of Malevich‘s paintings. While the south facade is an undulating, translucent glass skin through which passersby can see the activity inside the centre, making the museum welcoming and integrated with the city’s life; the east facade (along Walnut Street) is a sculptural relief made of blackened aluminium and concrete panels which expresses the jigsaw puzzle of gallery spaces within.

The ground floor of the lobby is designed as an Urban Carpet, a continuous surface that starts at the corner of the street, curves gently upward as it enters the building, and rises to become the rear wall of the museum. This feature is intended to visually and conceptually draw pedestrian movement from the surrounding city fabric into the building’s interior and up into the gallery spaces above. It carries the magical touch of Hadid’s own style – a masterful use of curved lines. The appearance of potential instability is an intentional feature of the Deconstructivist architectural style, which is designed to challenge traditional norms and gives a sense of dynamism and movement.

Her style is popularly known as No Ninety Degree Architecture as the design accurately reflects her explicit rejection of the right angle (90 degrees). She argued that “life is not made in a grid” and that “natural landscapes do not have rigid corners“, advocating for the fluid, dynamic and curvilinear forms that became her signature style. This approach also earned her the nickname The inventor of the 89 degrees.

During her 36-year-long career, Hadid and her firm, Zaha Hadid Architects, worked on approximately 950 projects, including Phaeno Science Centre (Wolfsburg, Germany, 2005), The Bridge Pavilion (or Pabellón Puente, Zaragoza, Spain, 2008), Sheikh Zayed Bridge (Abu Dhabi, the UAE, 2010), London Aquatics Centre (2012) and Al Wakrah Stadium (Doha, Qatar, 2019), in 44 countries. Meanwhile, the Heydar Aliyev Cultural Centre (2013) in Baku, Azerbaijan is one of the finest examples of her Deconstructivist architecture.

Zaha Hadid cannot be evaluated only as an architect, as her creative output extended across art, design, urban planning and academia. She was a multidisciplinary visionary who applied her unique design language to a wide range of fields. Constant obstacles within the patriarchal social structure, repeated rejections of her designs (initially often labelled unbuildable) and personal criticism, including comments on her hypersensitivity or thin skin, were significant challenges she faced throughout her career. However, those challenges did not keep her down. Instead, they shaped her resilient personality, strengthened her determination to push boundaries and pursue her unique vision, ultimately leading to global acclaim and historic achievements.

During the first Gulf War, Hadid attended a ceremony at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design. When a high-ranking US official asked her to put out her cigarette, Hadid replied: “I’ll stop smoking when you stop bombing Iraq.” Her reply helps one to get an idea about her strong personality and also about her stance on global political issues, particularly those concerning her home country, Iraq.

Boundless Ocean of Politics on Facebook

Boundless Ocean of Politics on Twitter

Boundless Ocean of Politics on Linkedin

Contact us: kousdas@gmail.com