India-US Trade Deal Seals Farmers’ Slide

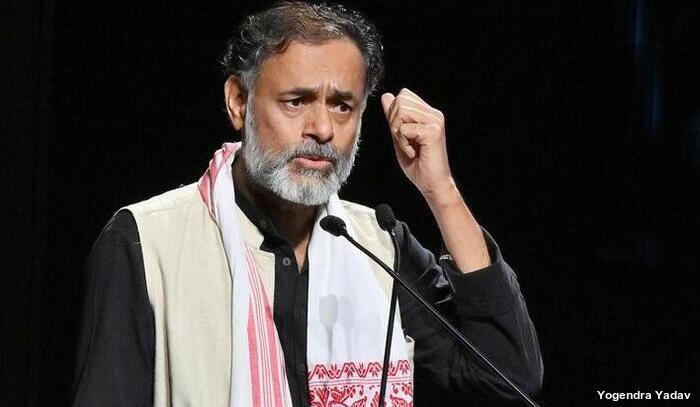

by Yogendra Yadav

A passing reference in the Budget speech signalled a paradigm shift in the Indian State’s relationship with farmers. The decision to include agriculture in the Indo-US deal confirms this transformation. This was not an overnight shift. It has been a long journey for the Indian farmer – from being the provider of the family to being a distant and poor relative. The understanding of what is their due has also shifted – from a fair share in the national resources to some compensation or a discount to now just a dole. It’s now a patron-client relationship: The state offers discretionary support for bare survival and the farmer offers loyalty, silence and votes. For the Indian State, farmers are now expendable, except as voters.

In her budget speech this year, Finance Minister of India Nirmala Sitharaman announced this departure with a loud silence. She did away with the ritual of paying homage to the kisan (farmer) and announcing grand-sounding but token schemes for the farmers. This year, the fleeting reference to the farmers in her Budget speech was in enunciating the third “kartavya” (duty) where farmers, people from the Northeast and those with physical and mental disabilities were bunched together. Don’t ask me for the FM’s economic rationale. But note the shift in tone: From “annadata” (food giver), the farmers are now “bechara” (poor fellow).

The budgetary allocations reflect this reading. The share of the government’s actual expenditure on Agriculture and Allied Activities as a percentage of its total expenditure has fallen consistently from 4.19% in 2019-20 to 3.06% in 2025-26 (revised estimate) and is budgeted at 3.04% this year. If you take out the Kisan Samman Nidhi, the expenditure on all other agriculture-related budget heads has fallen from 2.73% in 2018-19 to 1.78% in 2025-26 (budgeted at 1.85% in 2026-27). As agricultural scientist G V Ramanjaneyulu has pointed out, the Budget was “curiously disconnected” from what the government identifies as the immediate and long-term challenges of Indian agriculture – low income, high indebtedness and poor irrigation, besides soil degradation, groundwater depletion and climate change. In “new” India, farmers are not partners in growth and development. They are, at best, shock absorbers in managing food security and inflation. Otherwise, they are a burden, a cost centre to be minimised.

You may also like: A Costly Surrender

The decision to trade away farmers’ interests in the India-US trade deal is yet another confirmation of the place of farmers in the new scheme of things. While some ground was conceded in the Free Trade Agreements with Australia and the European Union (EU), especially on wines and processed food, the deal with the US involves a fundamental departure from the established policy of keeping food and farm produce out of international trade treaties. The US had little interest in the long list of agricultural products rattled off by the Indian ministers that are not included in this deal. It has managed to push the Indian Government to get what it wanted – a big chunk of India’s fast-growing animal feed market that could substitute China’s reduced import of corn and soyabean from the US.

The corn from the US, mostly genetically modified, will find its way in the form of Dried Distillery Grain and Solubles (DDGS). And genetically modified soybeans will be allowed as soya oil. Now we learn that “some pulses” are also part of the deal. Much more could follow. Sharp observers of Indian agriculture, such as Harish Damodaran, in this paper, and Harvir Singh of the portal Rural Voice, anticipate that this deal would seriously hurt makka (maize) and soybean farmers across the country who are already selling their crops much below the official Minimum Support Prices (MSP). The implications of this deal go far beyond what is visible in the joint statement, as it includes a provision to provide “deeper access” in the final agreement and a commitment by India to “address non-tariff barriers to the trade in US food and agricultural products”. The Alliance for Sustainable and Holistic Agriculture (ASHA-Swaraj) has expressed deep concern that this deal is “opening doors for import of a much larger spectrum of GM crops and food products”.

It would be unfair to blame just the present regime or the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) of Prime Minister Narendra Modi for turning their back on farmers. The new scheme of things is not so new. The post-Independence Indian State has never had a forward-looking vision for the farming community. Barring short-lived attention in the first Five-Year Plan or a lone voice, like former Prime Minister Chaudhary Charan Singh, the farmer has been an afterthought in India’s developmental planning. Policymakers have followed a borrowed and lazy belief that India would replicate the history of “developed” economies and most of the population would shift away from agriculture. In this vision, farmers are but a residue of the past. So, the best way to help a farmer is to help him to not remain a farmer.

This residual perspective has shaped the Indian State’s unwritten contract with the farmers, a coercive contract based on the farmers’ lack of alternative livelihoods and bargaining power. The state was focused on the quantum of agricultural production, not on the producer’s well-being. The price of staple food products was determined by the consumer’s need for cheap food grains and not by the farmers’ requirement of fair prices. Producers were made to subsidise consumers. Initially, the farmers were exhorted to produce more for the sake of the nation. Post-Green Revolution, this gave way to a selective bargain: You produce more, we ensure remunerative prices. The contract held only for a few regions and a handful of crops. Once the farmers began protesting in the 1980s against unremunerative prices, the contract was modified: You grow more, we offer subsidies. Instead of fair prices, the Indian State offered cheap electricity, free irrigation and subsidised fertilisers, and pushed the farmers into permanent dependency. This was enough to stigmatise the farmer over environmental pollution, electricity theft and freebies. We are witnessing the logical culmination of this process. Now the state is telling the farmer: You do what you like, we cannot wait for you. At most we can give you a dole, provided you give us votes.

This contract is unsustainable and unacceptable. The COVID-19 Pandemic reminded us that farmers are not dispensable. The agitation against the farm laws reminded us that farmers are not helpless. Many alternative experiments in agriculture all over the country remind us that they can have a different future. The challenge for the farmers is to weave a new politics with a different policy and an alternative perspective.

Boundless Ocean of Politics received this article, published in The Indian Express on February 11, 2026, from Yogendra Yadav. The author is the National Convenor of Bharat Jodo Abhiyaan and a member of Swaraj India, Swaraj Abhiyan and Jai Kisan Andolan.

Meanwhile,

Boundless Ocean of Politics on Facebook:

Boundless Ocean of Politics on Twitter

Boundless Ocean of Politics on Linkedin

Contact us: kousdas@gmail.com