Study: Early Humans May Have Kissed Neanderthals

Neanderthals disappeared around 40,000 years ago. Although the exact causes of their extinction are debated and are likely involved a combination of factors, such as climate change, competition with modern humans and potential diseases, scientists believe one of the reasons is their physical intercourse with primitive humans. Interestingly, the extinction of Neanderthals coincided with the spread of Homo sapiens across Europe and Asia that might have been exacerbated by a weakened magnetic field during this period.

A recent study has revealed that the earliest anatomically modern humans, Homo sapiens, appeared around 300,000 years ago in Africa, but the world’s first kiss had taken place “somewhere between 21.5 and 16.9 million years ago“, well before the existence of humans! Scientists are of the opinion that kissing likely originated in the common ancestor of great apes over 21 million years ago, long before any single first kiss could be attributed to a specific individual. This particular behaviour, defined as non-aggressive, mouth-to-mouth contact without food transfer, is observed in many modern great ape species, including chimpanzees, bonobos and orangutans. The latest study strongly suggests that Neanderthals likely practiced kissing and might have even kissed modern humans. In other words, they not only enjoyed physical relationships with primitive humans, but also kissed them.

Scientists have claimed that Neanderthal genetics gradually merged with the ancestors of modern non-African humans through interbreeding (physical intercourse), a process known as introgression. However, it is unclear whether this is the cause of Neanderthals’ extinction. The DNA of modern humans outside of Africa contains 1-4% Neanderthal DNA, confirming that Neanderthals interbred with early modern humans as they migrated out of Africa. However, there has not been much research into whether Neanderthals and early modern humans engaged in kissing. Researchers from Oxford University and the Florida Institute of Technology recently shed light on this issue as their paper has been published in the Journal of the Human Behavior and Evolution Society.

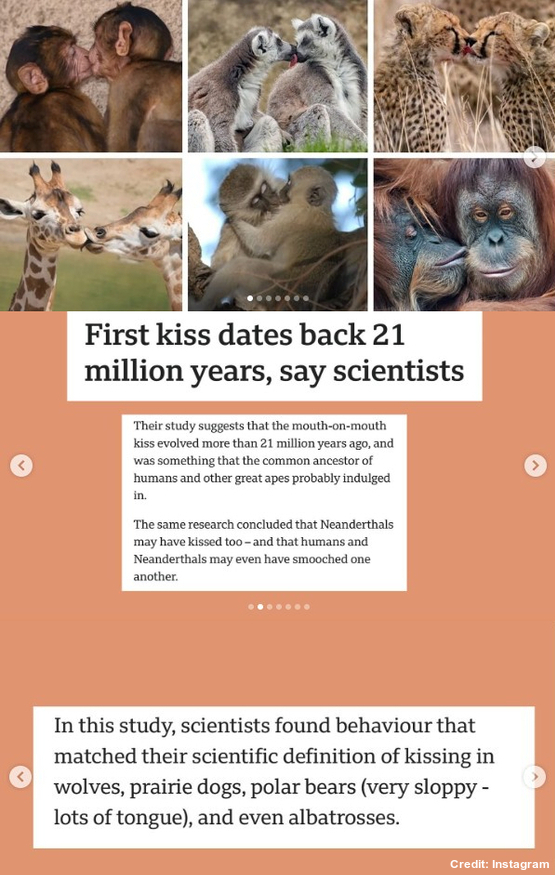

Many animals engage in behaviours that resemble human kissing, primarily for social bonding, affection, reconciliation or to assess a mate’s health. While these “kissing-like behaviours” may not always carry the same romantic connotations as in humans, they serve important social and biological functions within their species. Several animals often exhibit mouth-to-mouth or kissing-like behaviours for reasons that include aggression or dominance, food sharing and social bonding. It may be noted that such a behaviour in Kissing Gouramis (Helostoma temminckii) is not a form of affection, but rather a territorial display or ritualised fighting behaviour. The fish lock their large, fleshy mouths together and push against each other to establish dominance or a social hierarchy within their environment.

Hence, researchers have created a specific definition of what constitutes a kiss for the purposes of this study. They have decided to consider lip-to-lip contact between two creatures as kissing. Dr Matilda Brindle, an Evolutionary Biologist and the Lead Researcher, has stressed: “Kissing is defined as non-agonistic interactions involving directed, intraspecific, oral-oral contact with some movement of the lips/mouthparts and no food transfer.” This precise operational definition is crucial for maintaining consistency and objectively measuring the behaviour across the research population. It also allows the researchers to differentiate between kissing and other common animal behaviours, involving the mouth or face, such as grooming, feeding or fighting. By focussing strictly on lip-to-lip contact, the study establishes clear criteria for data collection and subsequent analysis of the social interactions among the species observed.

Researchers have also made an attempt to find the origin of kissing at different stages of evolution with the help of Bayesian Model, a statistical framework that updates beliefs about a hypothesis or model as new evidence becomes available. They have used this model a million times to make the results as accurate as possible. Interestingly, kissing-like behaviour is found not only in humans, but also in gorillas, chimpanzees, bonobos, polar bears, wolves and albatrosses, suggesting that it might be an ancient behaviour shared by a common ancestor. Dr Brindle has explained: “Humans, chimps and bonobos all kiss. It’s likely that their most recent common ancestor kissed. We think kissing probably evolved around 21.5 million years ago in the large apes.” A previous piece of research on Neanderthal DNA showed that modern humans and Neanderthals shared an oral microbe – a type of bacteria found in our saliva. “That means that they must have been swapping saliva for hundreds of thousands of years after the two species split,” she added.

The main aim of Dr Brindle and her co-researchers was to trace the history of early human kissing. After finding evidence of other animals engaging in kissing, researchers managed to construct an “evolutionary family tree” to work out when it was most likely to have evolved. Dr Brindle has stated: “The fact that humans kiss, the fact that we now have shown that Neanderthals very likely kissed, indicates that the two (species) are also likely to have kissed.” She told CNN: “Kissing is one of these things that we were just really interested in understanding. It’s pervasive across animals, which gives you a hint that it might be an evolved trait. With that information, we can kind of travel back through time.”

Scientists have mainly conducted the research on great apes on the basis of an old research paper on Neanderthal DNA. They have found that modern humans share a bacterium, Methanobrevibacter oralis, with Neanderthals that is transmitted through saliva. Genetic evidence shows the strains of this oral microbe in both species did not diverge until 112,000 to 143,000 years ago, well after humans and Neanderthals split, implying continued contact and exchange of saliva between the two groups. “Both species (Neanderthals and early humans) shared the same oral bacteria for over 100,000 years,” stressed Dr Brindle, suggesting saliva exchange. Although the researchers are yet to reach a definitive conclusion about why Neanderthals and apes kissed, they have speculated that “kissing might have helped assess a partner’s health and suitability for reproduction, increasing breeding success while strengthening bonds and trust” based on evolutionary theories.

The researchers have come to the conclusion that kissing was not merely a “romantic act”, but an evolutionary strategy for survival and reproduction that has persisted since ancient times. Now, Oxford University researchers have expressed hope that their research might open new horizons for finding out its real causes.

Boundless Ocean of Politics on Facebook

Boundless Ocean of Politics on Twitter

Boundless Ocean of Politics on Linkedin

Contact us: kousdas@gmail.com