Last Supper And No Resurrection: Godard

He opted for euthanasia and ended his life four years ago as he was convinced that there was nothing more to offer. Before leaving this world, he mentioned in his ambiguous voice, best suited to him, in L’histoire du cinéma (The history of cinema; 1988-99) that cinema gives Orpheus the right to look back, irrespective of the demise of Euripides. What if Jean-Luc Godard (December 3, 1930 – September 13, 2022) returns today…

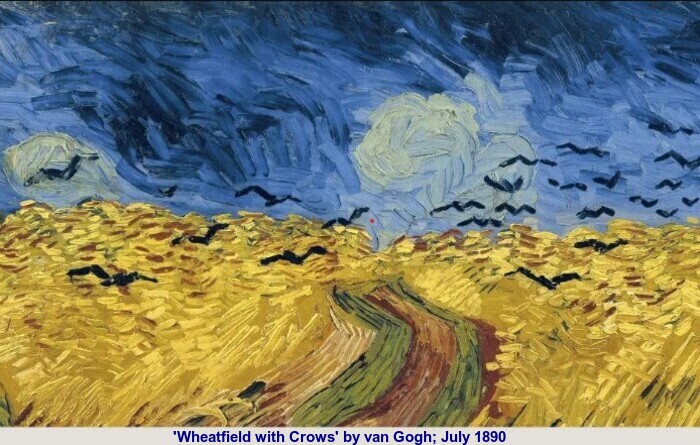

All of us know that it won’t happen. There are ages between Orpheus and Godard or the facts and the myths. The 1960s, 70s and 80s witnessed anger, as well as tears, euphoria and melancholia. However, Pierrot le Fou (Pierrot the Fool; 1965), Faut rêver Mozart (For Ever Mozart; 1996) and Notre musique (Our Music; 2004) still remain immortal. Van Gogh (March 30 1853 – July 29, 1890) released crows over a wheat field in a momentary dispersal on the frame in his final days. And, one discovered the crisis of civilisation in Bosnia and shattered Babylon. Even today, we are witnessing a similar situation in Gaza. How prophetically Aldous Huxley composed his 1936-novel Eyeless in Gaza! Godard, like a terrified assassin, left an indelible question for any establishment: Who is next to Kafka in your office?

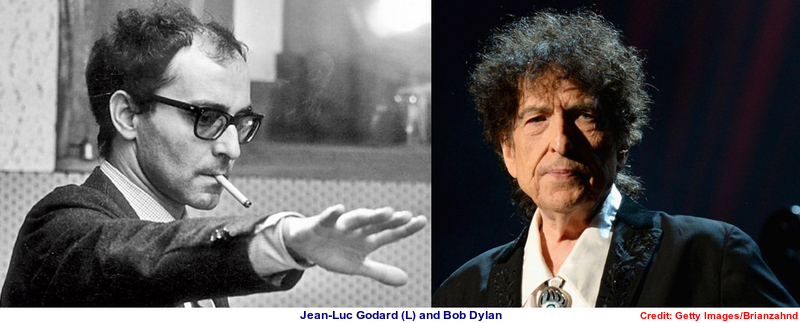

This is useless to discuss the influence of Godard. Both his admirers and critics, followers and enemies alike, know whether he was a piece of genius or a cunning showman. The saints, as well as the atheists, have accepted the fact that Godard was not just a filmmaker, but a cultural graffiti of the 20th Century, like Pablo Picasso (October 25, 1881 – April 8, 1973) and Bob Dylan (b. May 24, 1941). Quentin Tarantino has rightly said: “Godard did to movies what Bob Dylan did to music: they both revolutionised their forms.” He explained: “That’s one aspect of Godard that I found very liberating – movies commenting on themselves, movies and movie history.”

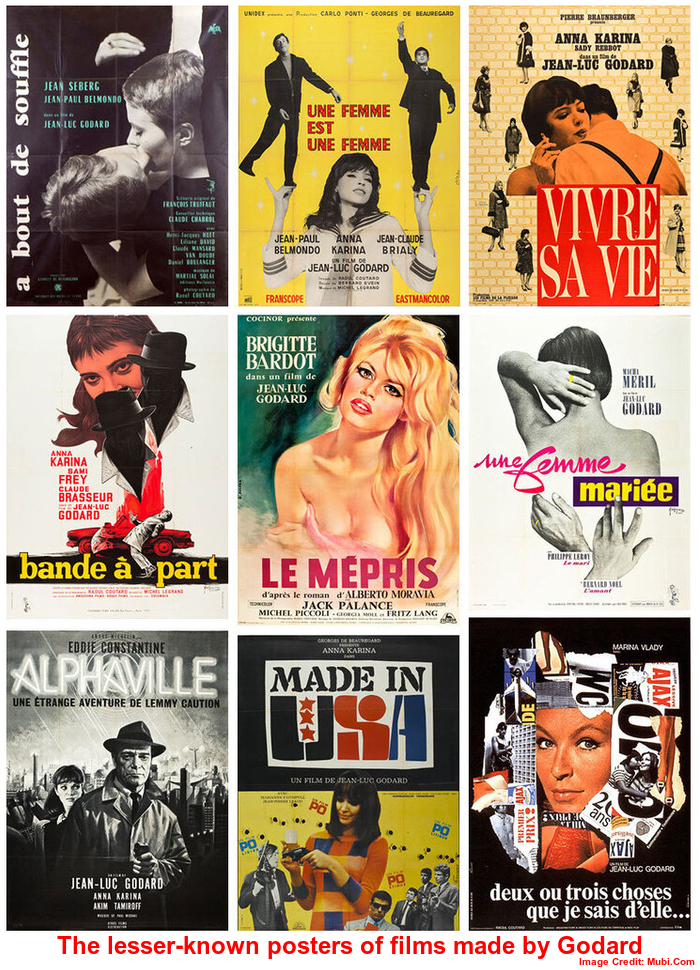

Interestingly, Godard began his journey in a simple manner. A little linguistic mistake made him internationally famous after the release of his first full-length feature film, Breathless, in 1960. The mistake was basically a misunderstanding of the film’s non-conventional dialogue and its revolutionary stylistic elements, which created a unique and influential cinematic experience that didn’t adhere to traditional linguistic or storytelling norms. Those, who once considered Picasso as the funeral procession of French art, considered the flaw as a grammatical error and an improvident atheism. Just as Picasso had created a specific form of abstract paintings, called collage, by connecting something tangible, Godard discovered the countless tangles of cultural ideas while exploring a different style of story-telling.

Godard played a crucial role in introducing us to the La Nouvelle Vague (The New Wave), an influential film movement in the late 1950s and early 1960s characterised by experimental and innovative filmmaking that broke away from conventions. He used to consider La Nouvelle Vague as a melancholic regret for a genre of movies which had already become obsolete. When Godard, (François Roland) Truffaut and some others made an attempt to dive into a modern life, disintegrated nearly seven decades ago, they decided to rescue cinema from its decade-old tendency to follow a classical and cohesive form of art. Just like paintings and literature, the language of their films did not derive only from an anti-Hollywood stance. Godard tried to overcome the fear of the material world and the terror of the world of commodities not only through images. Instead, he attempted to locate the other. Hence, he stressed: “I need an ‘other’ so as not to be afraid of the image of myself.“

When the history of cinema was writing a vast chapter for this French-Swiss director, screenwriter and film critic, he might not secure his place in the same league with Ingmar Bergman, Luis Buñuel, Michelangelo Antonioni and Andrei Tarkovsky in terms of artistic excellence. It is because Godard experienced a number of disastrous downfalls, apart from showing an unforgettable stupidity. Yet he became unmatched by utilising time in a perfect manner. In a sense, he questioned almost everything, from phonetics, sausages, sculpture to underwear, in the history of cinema. It seems that Godard is a modern Hamlet in a different attire.

After spending more than eight decades on earth, Rabindranath Tagore, the great Indian poet and philosopher, suddenly woke up near the Roopnarayana River, saying: “Words can only be fertilised by their meaning.” The matured Godard, too, discovered this intimate connection as if nature is a temple and people can reach there only after crossing various symbols. That language is as vast as the darkness and as noble as purity. Although Godard’s love for the written form of language is quite evident, the language of his films is hopelessly image-centric. The way Arthur Rimbaud explored the colour of vowels or James Joyce stressed on polyphonic narrations in his novels, Godard started making an attempt to incorporate a kind of literariness into films in the mid-1960s.

In his early youth, Godard quoted his teacher, French philosopher and essayist Brice Parain (March 10, 1897 – March 20, 1971) as saying: “The sign forces us to see an object through its significance.” Yet the sign (or symbol) changes repeatedly. Through the nakedness of the dog, named Roxy, which accompanied Godard on his journey; the creator wanted to show that the adjective naked contains different meanings in case of human and non-human relationships. In other words, language or words have limitations, as well as artificiality.

A filmmaker can identify reality on the basis of legends. While defining the nature of photography, André Bazin, a theorist of Realism, claimed that our desire for tangible reality comes out not only from reason, it has strong psychic motivation. He considered the tendency to imitate especially in post-Renaissance European representation and came to the conclusion that “perspective is the Original Sin of Western paintings“. Perhaps, Godard’s concept of tangible dimension is a perfect illustration of how tragic this Sin is. For example, his Adieu au Langage (Goodbye to Language; 2014) is a three-dimensional film full of dense reality. It can be said that such an initiative is nothing, but a philosophical facetiousness for an artist as Godard didn’t use the 3-D space to create a terrifying monster or an imaginary palace. Its tragic grandeur is quite understandable in our digital era.

Like his beloved poet Louis Aragon (October 3, 1897 – December 24, 1982), Godard used to believe that the history of poetry (young cinema) is ultimately the history of its technique. Furthermore, the language of cinema is heavily dependent on technology. Hence, Godard didn’t retreat. Instead, he mastered the techniques of modernity with unparalleled courage. For example, one can mention the low-angle tracking at the very end of the film Adieu au langage (Goodbye to Language). One may fail to understand where to look and how to look. A few moments after watching the scene, the person could realise that the focus is actually far away (from the perspective of the viewer’s focal point). Once, Godard panned the camera to show a three-dimensional image as the sum of two two-dimensional images. In fact, he simultaneously used the three-dimensional format and suspected it in an attempt to change the way one sees things.

Godard was not just a craftsman or a magician. While his male character believes that emptiness and infinity are his greatest inventions, the female character thinks only about physical relationship and death. Godard pondered the mortality of man and his thoughts, as it seems, could be the narrative of a defeated soul. Yet people attain that stage after spending many sleepless nights. Gradually, they approach the tomb of God through dense fog. Godard might have wanted to respond to Baudelaire‘s proposal with flowers of sin. However, looking at his life, it becomes clear that no one could say anymore that “Marian, you are a melancholic night” or “Anna Karina is just some pieces of flesh“. As the fading lady appears to be a speedy dear, it can no longer be said that she is the eternal constellation in the darkness.

Godard rightly realised that there was no Beatrice in this hellish journey as it was just a tale of a poor sailor standing at the helm of a ship. For us, the filmmaker, staying alone in the womb of hell, became the gatekeeper of a failed civilisation which was on the brink of apocalypse. His concept of anarchy can be compared to religious chants only. Godard encountered a number of downfalls and failures. Still, he secured a unique place in the history of world cinema by encouraging people to think of a fascinating aesthetic medium, like film, as a philosopher. He himself might be a philosopher of restaurant (or public intellectual), like Slavoj Žižek. However, there is always a search for an infinite, an immeasurable and an other in his works.

That’s why no one can forget Godard. He is one of the few who could purify the insignificance or triviality with fire. Even philosophers become cold and the empresses of love become grey. Fortunately, Godard still remains luminous.

Translated by Koushik Das from the original Bengali article penned by Sanjoy Mukhopadhyay. Mukhopadhyay is a Professor (Retired) of Film Studies at Jadavpur University, Kolkata, India and a Ritwik Ghatak scholar. He is famous for his writings on cultural modernity in India. Mukhopadhyay is also a commentator on social issues.

অন্তর্ঘাতনার পুণ্য: গোদার

এই তো বছর চারেক আগে তিনি স্বেচ্ছামৃত্যু বরণ করলেন। অথচ ‘এসতোয়ার দ্যু সিনেমা’ বা সিনেমার ইতিহাসে তিনি আমাদের জানিয়েছিলেন যে, চলচ্চিত্র অরফিউস-কে অধিকার দেয় পিছন ফিরে তাকাতে। ইউরিপিডিসের মৃত্যু ব্যতিরেকেই। আজ যদি গোদার ফিরে আসেন…

আসবেন না তা আমরা জানি। অরফিউস থেকে গোদার— তথ্য থেকে কাহিনি— মধ্যে পড়ে রইল দীর্ঘ কয়েক দশক। ষাট-সত্তর-আশি, রাগের শেফালিকাপুঞ্জ, অশ্রুর অববাহিকা— রয়ে গেল অমরতার শিখরে ‘পিয়ের লো ফ্যু’, ‘নোত্র মুজিক’। একদিন ভ্যান গখ স্থিরচিত্রের পটে মৃত্যুর আগের মুহূর্তে গম-ক্ষেতে উড়ন্ত কাকেদের মুক্তি দিয়েছিলেন ক্ষণিকের বিচ্ছুরণে। আর আমরা দেখলাম, বসনিয়া ও চূর্ণ ব্যাবিলনে, হয়তো-বা আজকের গাজায়, সভ্যতার সংকট বিষয়ক মর্মান্তিক প্রতিবেদন। তিনি সন্ত্রস্ত আততায়ীর মতো অমোঘ প্রশ্ন রেখে যান যে-কোনও প্রতিষ্ঠানের প্রতি— হু ইজ নেক্সট টু কাফকা ইন ইওর অফিস?

Read: The Gospel Of Uncertainty

তাঁর প্রভাবের কথা আমাদের বলার দরকার নেই। যাঁরা তাঁর বিরোধী, যাঁরা তাঁর স্বপক্ষে— সকলেই জানেন যে, গোদার প্রতিভা না চালাকি এই প্রশ্ন আজ অবান্তর। পৌত্তলিক ও নাস্তিক, উভয় পক্ষই মেনে নিয়েছেন গোদার আর নেহাত চলচ্চিত্র-স্রষ্টা নন, বরং বিশ শতকের ইতিহাসে একটি সাংস্কৃতিক গ্রাফিত্তি। যেমন পাবলো পিকাসো, যেমন বব ডিলান। তারান্তিনো ঠিকই বলেছেন যে, সিনেমায় গোদারের অবস্থান অনেকটা তেমনই, বব ডিলান যে-রকম সংগীতে। দু-জনেই মাধ্যমের আকার বা আত্মা বদলে দিতে পেরেছেন।

এই বদলে দেওয়ার পথে গোদার-কে দেখে আমাদের মনে হয়, কী সামান্যভাবেই না শুরু হয়েছিল! একটু ভাষার ভুল কীরকম আন্তর্জাতিক খ্যাতিসম্পন্ন হয়ে উঠেছিল, তার প্রথম পূর্ণদৈর্ঘ্য কাহিনিচিত্র ‘ব্রেথলেস’ মুক্তির পরে। যাঁরা একদিন পিকাসো-কে দেখে মনে করেছিলেন ফরাসি চারুকলার অন্তর্জলি যাত্রা, তারাই গোদার-কে দেখে মনে করলেন ব্যাকরণের ভুল ও এক অপরিণামদর্শী নাস্তিক্য। আসলে বিমূর্ততার মহাসমুদ্রে পিকাসো যেমন সাকার কোনওকিছুর সংযোগে একদা কোলাজ নামের নক্ষত্রবীথির পত্তন করেন, গোদার-ও তেমন সংস্কৃতি বিষয়ক ভাবনার অজস্র জট উন্মোচিত করার ফাঁকে-ফাঁকে রেখে যান ভঙ্গুর কাহিনি— পথের ইশারা।

Read: A Terrible Laughter: Milan Kundera

গোদারের কথা ভাবলে ফরাসি নবতরঙ্গের কথা এসেই যায়। কী ছিল এই Nuvelle Vague? ‘অনস্তিত্ববান সিনেমার জন্য বিষণ্ণ অনুশোচনা’ এই শব্দক’টির মধ্য দিয়ে গোদার নবতরঙ্গ বিষয়ে তাঁর ধারণা ব্যক্ত করেছেন। আজ থেকে প্রায় ৭৫ বছর আগে ত্রুফো-সহ সবান্ধব গোদারের মনে হওয়া একটি যথার্থ ভগ্নাংশে বিভাজিত আধুনিক জীবনে ডুব দিতে চাইলে, চিত্রকলা ও সাহিত্যের মতোই সিনেমাকেও সমতলীয় হওয়ার ধ্রুপদী স্বভাব ভুলে যেতে হবে। এই ভাষা শুধু হলিউড-বিরোধিতা থেকে নয়। জড়ের পৃথিবীতে যে ভয়, পণ্যের পৃথিবীতে যে আতঙ্ক, তা থেকে মুক্তির আকাঙ্ক্ষায় গোদার প্রতিচ্ছায়া চান না, কিন্তু এক অপরকে খুঁজে চলেন: ‘I need an other so as not to be affraid of the image of myself’.

যখন চলচ্চিত্রের ইতিহাস এই সুইস-ফরাসি শিল্পীর জন্য এক প্রশস্ত অধ্যায় রচনা করেছে তখনও শিল্পের উৎকর্ষে তিনি যে বার্গম্যান, বুনুয়েল, আন্তেনিওনি, তারকভস্কির পাশে হাঁটেন তা নয় কারণ গোদারের অনেক রক্তাক্ত পতন ও ক্ষমাহীন মূঢ়তা আছে। তবু তিনি অবিস্মরণীয়, কারণ সময় তার বাহুলগ্না, সেই সূত্রে তিনি ছায়াছবির ইতিহাসে সবচেয়ে আর্তপ্রশ্নকারী। ধ্বনিতত্ত্ব থেকে সসেজ, ভাস্কর্য থেকে অন্তর্বাস, সবই তাঁর জিজ্ঞাসার অন্তর্ভুক্ত। তিনি পোশাক বদলে আধুনিক হ্যামলেট।

Read: Salvador Dalí: The Sentry Of Hell

পৃথিবীতে আশি বছরের বেশি সময় কাটানোর পরে রবীন্দ্রনাথ রূপনারাণের কূলে জেগে উঠে বলেছিলেন, শব্দ শুধু শব্দের অর্থে নিষিক্ত হতে পারে। পরিণত গোদার, অন্তিম গোদার আবিষ্কার করেন অন্তঃসলিলা সেই যোগাযোগ। প্রকৃতি যেন এক মন্দির, মানুষ যেখানে আসে প্রতীকের অরণ্য পেরিয়ে। সেই ভাষা ‘নিশীথের মতো ব্যাপ্ত, স্বছতার মতো মহীয়ান’। গোদারের মূল সংকট হচ্ছে ভাষার লিখিত রূপের প্রতি তাঁর অনুরাগ প্রামাণ্য হলেও, চলচ্চিত্রকারের ভাষা নিরুপায়ভাবে চিত্রধ্বনিময়। রাবোঁ যেভাবে স্বরবর্ণের রঙ খোঁজেন, জয়েস যেভাবে লেখেন, গোদার তা লক্ষ করে এক ধরনের ‘সাহিত্য-ত্ত্ব’ সিনেমায় জড়িয়ে নেওয়া যায় কি না, সে-ই মধ্য-ষাট থেকে সেই প্রয়াস চালিয়ে গিয়েছিলেন।

তারও আগে, যৌবনারম্ভে তাঁর শিক্ষক, ভাষা-দার্শনিক ব্রিস পারঁ-কে উদ্ধৃত করে জানিয়েছিলেন, ‘চিহ্নই আমাদের বাধ্য করে অর্থদ্যোতনার মধ্য দিয়ে বস্তুকে দেখতে।’ তবু এই চিহ্ন বারবার বদলায়। মহাপ্রস্থানের পথে যে-সারমেয়টি গোদারকে সঙ্গ দেয়, তার নগ্নতা প্রসঙ্গে স্রষ্টাও দেখাতে চান, ‘উলঙ্গ’ বিশেষণটির তাৎপর্য নর বা নারীর ক্ষেত্রে যা, কুকুর বা অন্যান্য মনুষ্যেতর প্রাণীদের মধ্যে তা নয়। শব্দের সীমানা আছে, কৃত্রিমতাও আছে।

Read: The Lethal Power Of Silence

চলচ্চিত্রকার জনশ্রুতি অনুযায়ী বাস্তবকে শনাক্ত করতে পারেন। বাস্তববাদী তাত্ত্বিক আন্দ্রে বাঁজা আলোকচিত্রের স্বরূপ নির্ণয় করতে গিয়ে দাবি করেছিলেন, মূর্ত বাস্তবের প্রতি আমাদের আকাঙ্ক্ষা যতটা মানসিক, ততটা যৌক্তিক নয়। রেনেসাঁস-উত্তরপর্বে ইউরোপীয় প্রতিরূপায়ণে নকল করার প্রবৃত্তি দেখে তাঁর মনে হয়েছিল ‘পরিপ্রেক্ষিতই পশ্চিমি চিত্রকলার আদি পাপ।’ এই পাপ যে কতদূর মর্মান্তিক, তার একটি উপযুক্ত দৃষ্টান্ত হিসেবে হয়তো গোদার স্পর্শগ্রাহ্য আয়তনের কথা ভেবেছেন। কারণ ‘আদিউ লাগাঁ’ ত্রিমাত্রিক, তাতে ঘনবাস্তবতার স্বাদ। বলা চলে একজন শিল্পীর পক্ষে এই উদ্যোগ এক দার্শনিক ফিচলেমি। গোদার তো থ্রিডি বলতে দুর্ধর্ষ দানব অথবা শিশুতোষ প্রাসাদ বানালেন না। আজকের ডিজিটাল যুগে তার মর্মান্তিক মহিমা বোঝা যায়।

তাঁর প্রিয় কবি লুই আরাগঁ-র মতোই তিনিও অনেকটাই বিশ্বাস করেন, কাব্যের (তরুণ চলচ্চিত্রের) ইতিহাস শেষপর্যন্ত তার টেকনিকের ইতিহাস। উপরন্তু সিনেমা বিশেষ ভাবেই প্রযুক্তি নির্ভর ভাষা। সুতরাং, গোদার পিছিয়ে আসেন না। অসমসাহসে আধুনিকতার প্রয়োগকৌশল রপ্ত করেন। যেমন ধরা যাক, ‘বিদায় ভাষা’ ছবিটির শেষে লো-অ্যাঙ্গেল ট্র্যাকিংয়ের কথা। আমরা বুঝতেই পারি না, কোথায় দেখব, কীভাবে দেখব। একটু পরে যেদিকে চোখ রেখেছিলাম, তার পরিপ্রেক্ষিত বোঝা যায়, ফোকাস আসলে দূরে আছে। একবার ক্যামেরা প্যান করে গোদার একটি ত্রিমাত্রিক ইমেজ-কে দু’টি দ্বিমাত্রিক ইমেজের যোগফল হিসেবে দেখাতে চান। অর্থাৎ, গোদার একইসঙ্গে ত্রিমাত্রিক ফরম্যাট ব্যবহার করেন ও তাকে সন্দেহ করেতে থাকেন। বস্তুত, তিনি আমাদের দেখার সংস্কার পালটে দিতে চান।

Read: Constructing & Deconstructing The Refugee Issue!

তবু তো তিনি কারিগর বা জাদুকর নন শুধু। যেখানে পুরুষ চরিত্রটি বিশ্বাস করে শূন্য আর অনন্ত মানুষের শ্রেষ্ঠ আবিষ্কার, সেখানে নারীচরিত্রটি ভাবে যৌনতা আর মৃত্যু। গোদার মানুষের নশ্বরতা বিষয়ে ভেবেছেন এবং এই ভাবনা, এখন মনে হয়, হতে পারে পরাভূত আত্মার বিবরণী। তবু মানুষ সেখানে আসে দীর্ঘ শ্রমের নিদ্রাহীন রাত্রি পেরিয়ে। গাঢ় কুয়াশার মধ্যে তিনি ঈশ্বরের সমাধিভূমির কাছে চলে আসেন, আসলে তিনি হয়তো চেয়েছিলেন, ব্যোদলেয়ারের প্রতিপ্রস্তাব হিসেবে ‘পাপের ফুল’। কিন্তু তাঁর জীবনের দিকে তাকালে বোঝা যাবে, বলা গেল না আর মারিয়ান: আর্ত রাত্রি তুমি। আনা কারিনা মাংসের কুসুম— হরিণীর মতো সেই নারী চলে গেছে তার জীবন থেকে— আর বলা যাবে না অনন্ত নক্ষত্রবীথি তুমি অন্ধকারে।

গোদার বুঝতে পেরেছিলেন, এই নরক সরণিতে কোনও বিয়াত্রিচে নেই, এই আখ্যান জাহাজতিমিরে দাঁড়িয়ে থাকা এক নাবিকের বিধুর রোজনামচার গল্প। একা, নরকের জরায়ুতে গোদার আমাদের কাছে হয়ে ওঠেন ধ্বংসের প্রান্তে উপনীত এক ব্যর্থ সভ্যতার দ্বাররক্ষী। তাঁর নৈরাজ্য মন্ত্রোচ্চারণের নামান্তর। গোদারের অনেক পতন এবং ব্যর্থতা আছে। তবু তিনি যে স্মরণীয় অনন্য, তা এ-জন্যই যে, তিনি সিনেমার মতো এক চটুল রূপোপজীবিনীকে দার্শনিক ভাবতে চেয়েছিলেন। তিনি নিজে হয়তো রেস্তোরাঁর দার্শনিক-ই, জিজেকের মতো। কিন্তু সেই কথাবার্তার মধ্যে সবসময়েই খোঁজ থাকে এক অসীমের, এক অমেয়র, এক অপরের।

Read: Presenting ‘Selves’ As ‘Radical Art’

সে-জন্যই গোদার-কে আমরা ভুলতে পারি না। যে-ক’জন মানুষ তুচ্ছতাকে অগ্নিশুদ্ধি দিতে পেরেছিলেন, তার মধ্যে একজন তিনি। তার ফলে, বলাই যায়, দার্শনিকও হিম হয়, প্রণয়ের সম্রাজ্ঞীরা হবে না মলিন? গোদার ভাগ্যক্রমে এখনও অমলিন রয়ে গেছেন।

সঞ্জয় মুখোপাধ্যায়

Boundless Ocean of Politics on Facebook

Boundless Ocean of Politics on Twitter

Boundless Ocean of Politics on Linkedin

Contact us: kousdas@gmail.com